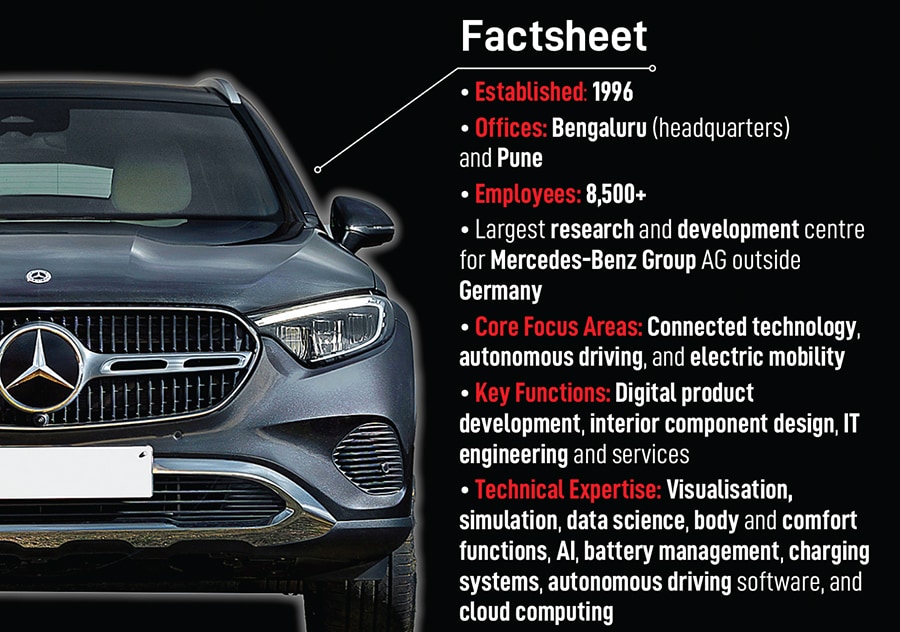

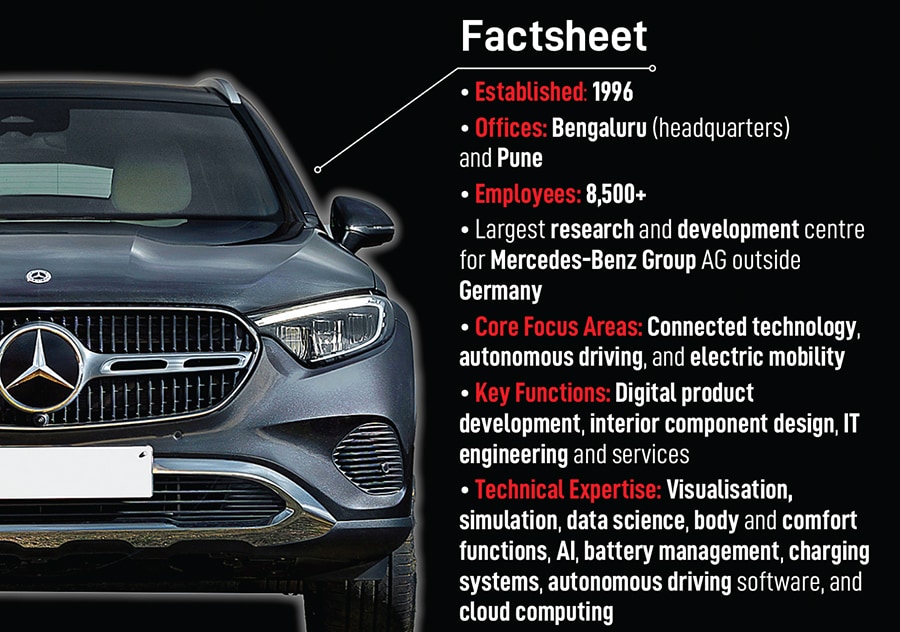

There is a little bit of India in every Mercedes vehicle across the world, and, if anything, he expects that little to grow manifold from now. Mercedes-Benz operates the Mercedes-Benz Research and Development India (MBRDI), the largest research and development centre for the Mercedes-Benz Group AG outside of Germany.

The company began operations in India in 1996, initially to provide back-end support for the automaker who had just stepped into Indian shores before growing it into a research and development centre that now employs over 9,000 people. The company’s focus is largely around the development of new technologies for connected, autonomous and electric vehicles.

In addition, it also lends itself to product design and development, computed aided engineering, electrical and electronics that includes chassis, driver assistance and telematics, among others. As vehicles become more technology-enabled, the R&D arm in India has emerged as a crucial arm for the German automaker.

In all, Mercedes sells a little over two million cars annually, of which India only accounts for a minuscule fraction. The country is currently the fifth largest in the Asia-Pacific region and is expected to emerge as the third largest, overtaking the likes of Turkey and Australia as wealth in the world’s fastest-growing economy surges.

However, the R&D arm’s vision and function far expand the domestic market. “We started in 1996 to help the IT part of the business in India,” says Saale. “But, over time, realised the charm of doing automotive and digital engineering. The good thing that happened for us on the way is that, like the aerospace industry, automotive engineering became highly dependent on digital engineering.”

That meant digital technology had begun to supersede much of the work that was being done physically, allowing a shift in technology patterns and in the process, creating digital twins. “Imagine for a moment that when you decide on a car line, you have the headquarters that follows up physically on the car and the location in India that follows up digitally on the car,” says Saale.

Mercedes’s tryst with the Indian shores began in 1994, when the Stuttgart-headquartered automaker brought its globally acclaimed W124 in 1994, importing it through a partnership with the Tata Group, and retailed it for around ₹20 lakh, a princely sum then.

Also read: How Mercedes Benz’s strategic patience made it India’s largest luxury carmaker

Then, even as many of its compatriots, including those from the US, Germany and South Korea, who came around the same time as Mercedes in India folded up, the German automaker held its ground choosing instead to set up an assembly plant in the country. It’s another story that the carmaker’s chief rivals, BMW and Audi, took another decade to understand the growing potential in India before it set foot in the country. The R&D arm began with helping the Indian business, before growing into its own.

“When a company starts to look at a certain location on the planet purely for its talent and competence, I think you have turned the leaf,” adds Saale. “And suffice to say that if there’s one location outside our headquarters that can actually put an entire car together for Mercedes-Benz, it’s sitting right here in India.”

Interestingly, it’s at the India facility that a lot of the crash testing for the vehicle is conducted on simulators before doing so physically, which helps cut down costs for the automaker. “Today, there are two types of GCCs (global capability centres) in the country,” Saale adds. “The larger set of companies that have the local market and need to have local R&D, people who’ve come in here purely for cost arbitrage, and companies like us, little fewer in that segment, who are here because the talent is exemplary.”

With more than 1,600 centres employing more than 1.5 million professionals and a projected market size of $110 billion by 2030, India’s global capability centres are fast growing across segments such as automobiles, aerospace, pharmaceuticals and technology.

“Engineering has gone digital like no time else before, and the demography, the education, the propensity to engage with young India is something that we want to harness on,” Saale says. “In your formative years, digital was following physical. Today, the mathematical models are so mature that digital proceeds physical mechanical engineering.”

That means, even to set up a factory, the India team builds the models, which are then tested before work begins on the ground. Then there is also the massive work that goes into developing electronic control units, especially as cars now become more connected. “A sophisticated car like a Mercedes S class, for example, boasts of more than 100 different electronic control units which means millions of lines of codes,” adds Saale.

Being close to the Indian market, where the automaker remains the largest luxury car maker, also means the team is privy to crucial customer data that helps in developing systems and models around the future of automobiles. India is also the fourth-largest automobile market in the world. Globally, automakers ranging from GM to BMW and Ford are expected to spend over $500 billion in developing all-electric vehicles from gasoline models over the next several years. In India too, automakers from Tata to Mahindra have taken the plunge to develop their models as the government looks to have 30 percent of all vehicles sold in the country to be electric by 2030.

Today, the company employs 9,000 people, mostly engineers, and another 5,000 contractors, working closely with the company. Last year, it also signed a five-year Master Research Agreement with Birla Institute of Technology and Science Pilani for advanced technology research. Says Saale, “We have moved from being just being wanting to be called a car company to a mobility provider and the depth of engineering that we had reached already gives us a space to play in all those segments from India.”

(This story appears in the 21 February, 2025 issue

of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)