Supam Maheshwari, Managing director and CEO, Brainbees Solutions

Supam Maheshwari, Managing director and CEO, Brainbees Solutions

Image: Madhu Kapparath

In early 2015, battlelines were drawn between the top two players in the childcare products business.

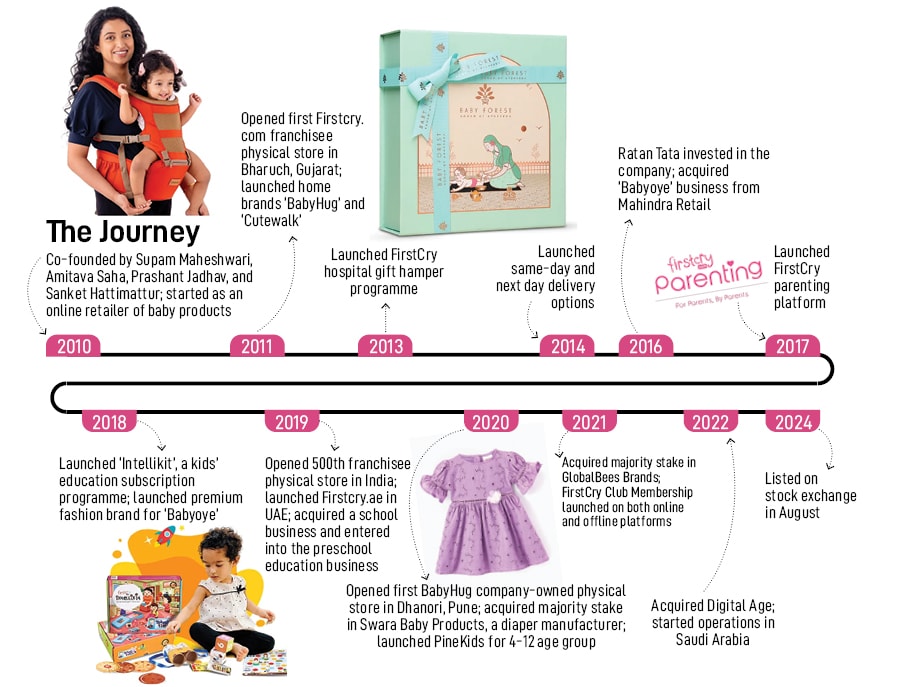

In February, FirstCry reportedly bagged $26-million funding in its Series D round. Backed by Valient Capital Partners, IDG Ventures India, Ventex Venture Holdings, and SAIF Partners, the company—which had started as an online retailer of children’s products in December 2010 and had over 100 franchisee stores across 85 cities—was looking to boost its offline presence. It made sense as India was in the midst of a retail boom and consumers flocked to brick-and-mortar stores.

In the same month, FirstCry’s rival—Mom & Me—was also out in the market with its shopping cart. Mahindra Retail, the owner of Mom & Me, bought BabyOye, which was backed by marquee venture and hedge funds such as Tiger Global Management, Accel, and Helion Venture Partners. The buyout made sense as Mom & Me, a predominantly offline brand, was sharpening its online play and BabyOye ticked all the boxes. By February, the retail arm of Mahindra & Mahindra reportedly operated over 100 Mom & Me stores.

Both the competitors were neck and neck, and Anand Mahindra, the chairman of the Mahindra Group, recalls the fierce fight. “We acquired BabyOye and were still fighting Supam Maheshwari (the co-founder of FirstCry),” Mahindra tells Forbes India in an exclusive interview.

Both the competitors were neck and neck, and Anand Mahindra, the chairman of the Mahindra Group, recalls the fierce fight. “We acquired BabyOye and were still fighting Supam Maheshwari (the co-founder of FirstCry),” Mahindra tells Forbes India in an exclusive interview.

Maheshwari, too, acknowledges the heat. “The competition was intense… it had always been intense,” says the managing director and CEO of Brainbees Solutions, the parent company of FirstCry (co-founded by Maheshwari, Amitava Saha, Prashant Jadhav, and Sanket Hattimattur). “When we started, Mom & Me was a much bigger rival.”

Five years later, the rivalry was amped up. Though both the players were bleeding, the bigger rival had a much bigger problem: Ballooning losses. In FY14, Mahindra Retail reportedly posted a revenue of ₹206 crore and a loss of ₹114 crore. The situation remained bleak over the next one-and-a-half years and somebody had to blink. In October 2016, FirstCry acquired the baby care business of Mahindra Retail. The rivals became partners and embraced consolidation over competition. “They were pragmatic, and that’s typical of the Mahindra Group,” says Maheshwari, alluding to the merger that pole-vaulted FirstCry as the bigger omnichannel retailer of baby products in the country.

The merger, though, was a win-win for both the players. If Maheshwari got his share of the bargain—a bigger entity and a free play to build an even bigger retail empire—the patriarch of the Mahindra Group, too, extracted his pound of flesh.

The merger, though, was a win-win for both the players. If Maheshwari got his share of the bargain—a bigger entity and a free play to build an even bigger retail empire—the patriarch of the Mahindra Group, too, extracted his pound of flesh.

Mahindra explains why he bit the bullet. In early 2016, one of his trusted lieutenants—Zhooben Bhiwandiwala—urged him to make peace. “One day, he came to me, and said, ‘Anand, I met Supam. The guy’s a genius, and we won’t be able to match him’,” recalls Mahindra. “We don’t have that fire in the belly like he does…why don’t you just meet him?” Bhiwandiwala also claimed that FirstCry’s distribution model was even better than Amazon’s.

When the meeting did happen, its outcome emerged in a minute. “We got sold on him, and we merged,” says Mahindra, who was the largest shareholder in 2016. “We created value.”

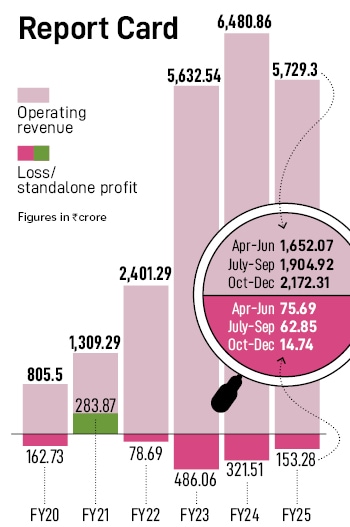

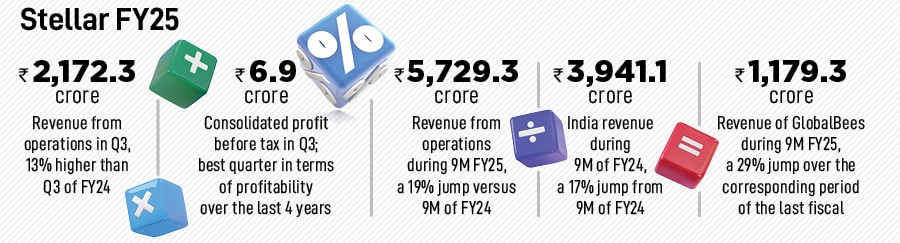

Eight years later, in August 2024, FirstCry created value for all stakeholders when it made its public market debut. The stock was listed at ₹651 on NSE, a 40 percent premium to the issue price of ₹465. Fast forward six months: Though the share price has tumbled to close to ₹410, FirstCry is still cruising on the journey of value creation. Its latest figures are a testament to its financial prowess: The third quarter of FY25 was the best in terms of profitability over the last four years (see box).

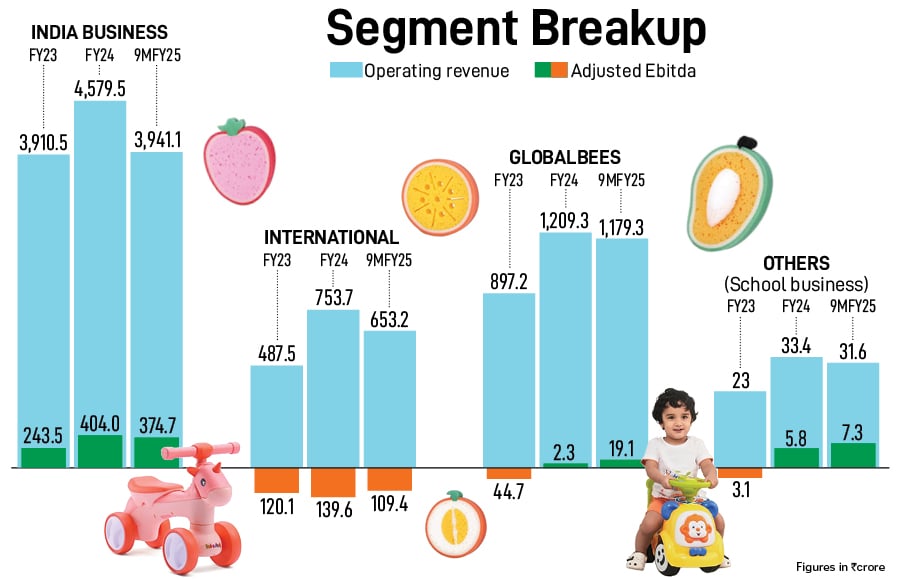

What is most gratifying is the way FirstCry has shaped up since 2020. Its operating revenue soared close to 8x, from ₹805.50 crore in FY20 to ₹6,480.86 in FY24. The losses, too, have moderated: From ₹162.73 crore in FY20, it reached a high of ₹486.06 crore in FY23 before falling to ₹321.51 crore the next fiscal. In the third quarter of FY25 (Oct-Dec), it posted a loss of ₹14.74 crore as against ₹48.4 crore in the corresponding quarter of the previous fiscal. “We have run a tight ship. We are frugal. It’s our DNA,” says Maheshwari. “Even after going public, we have continued with our fiscal discipline,” he adds.

Also read: Forbes India CEO of the Year: M&M’s Rajesh Jejurikar, the risk taker

What explains the staggering dominance of India’s biggest omnichannel retailer of children’s products? Maheshwari reveals the secret sauce. “We kept building strong and deep moats. It increased our chance of winning,” he says, outlining a series of contrarian bets taken by the serial entrepreneur.

In 2011, he recounts, the kids and baby products’ market was huge, fragmented, and unorganised. Though there was a battery of players, the demand and supply aggregation was still a blind spot for most of the players in the organised segment. Maheshwari sniffed an opportunity and built his first moat.

The second turned out to be the core of FirstCry: An omnichannel strategy. During the formative years of FirstCry, the market exhibited a strange behaviour. The online players focused only on online, while the offline players stayed true to their brick-and-mortar strategy. FirstCry, which rolled out its first offline store in June 2011, kept adding more stores.

For a player who was born online, going offline was tough on multiple counts. Maheshwari recounts the headwinds. To start with, ‘why are you building offline’ was the recurring question from his investors. The founder pleaded for more time and patience.

“We were not investing in offline. It was a franchise model,” he explains. So, the brick-and-mortar push didn’t need any capex (capital expenditure), opex (operating expenses), or working capital. “Please don’t stop us,” he implored the backers. A founder, reckons Maheshwari, must trust his instincts. “At times, investors might not have an operating view,” he says.

Another contrarian moat was building warehouses. “In 2011, nobody was building warehouses. Everybody went the third-party route,” he says. FirstCry shunned the herd mentality as Maheshwari felt that a consumer business is as much about product as about consumer experience. At a time when spending advertising dollars on Facebook and Google was the norm, Maheshwari created a distinct playbook. “We spent money on gift hampers,” he says, alluding to a first-of-its-kind consumer outreach and marketing strategy of rolling out a hospital gifting programme in 2013. The Pune-based company tied up with maternity and general hospitals in the city and offered gift boxes—it contained products like diapers, lotions, and baby wipes—to the parents of newborn babies.

“It was a masterstroke,” he asserts, adding that the programme was extended across the country. Result? The hampers led to strong conversions. “It helped in a big way in tackling CAC (consumer acquisition cost),” he says.

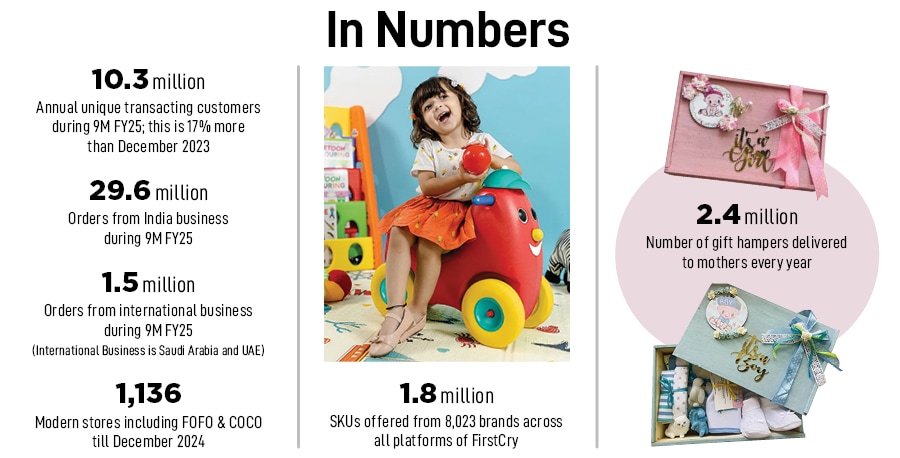

Based on data collected from the hospital gift hamper programme, the company underlined in its Draft Red Herring Prospectus (DRHP) filed in December 2023, FirstCry formulates automated campaigns. Personalised user engagement takes place through targeted advertisements, promotions, messages, banners, pop-ups, product suggestions and notifications, the company outlined in its draft ahead of its IPO in August 2024. Till June 2023, it had distributed over 16.8 million gift hampers across 13,000 hospitals in 514 cities. One-and-a-half years later, the programme continues in full swing. “We deliver close to 24 lakh hampers every year,” claims Maheshwari, adding that hampers helped develop an emotional bond and led to strong conversion. “The programme has been scaled to touch close to 14,000 hospitals,” he adds.

Gifts, though, were just one weapon to win customer loyalty. Another was its SKUs (stock-keeping units). “Today, we have over 18 lakh SKUs from 8,023 brands across all platforms of FirstCry. This gave us a massive edge,” reckons Maheshwari.

Then there are home brands—another moat—such as BabyHug, Babyoye, Cutewalk, and Pine Kids, which have helped the company reach out to a wide range of consumers with differentiated products. BabyHug, he claims, is the largest mothers’, babies’, and kids’ products brand in Asia Pacific (excluding China) in terms of product assortment.

Another trick in the book was to build a community of parents on its platform. The FirstCry platform, he underscores, is a one-stop destination for parenting needs across commerce, content, community engagement, and education. “Think of us as Expedia and Tripadvisor in a single app,” he says. “We are an emotional partner in a woman’s journey. This helped us in building a tangible relationship,” he adds.

FirstCry, reckon marketing and industry experts, is well poised to make the most of the boom in the childcare products market in India. The market is estimated to grow at a CAGR of 13-14 percent, from $31 billion in 2022 to $56-60 billion by 2027, according to Redseer Strategy Consultants.

Ashita Aggarwal, professor of marketing at SP Jain Institute of Management and Research, points out what has been fuelling this explosive growth—high disposable income, shorter product replacement cycles, high purchase frequency, shift to branded products, and increase in retail penetration across tier II and beyond have acted as tailwinds.

A fragmented supply with a lack of specialty brands in the childcare segment in India has worked in the favour of FirstCry. “Its content strategy creates a strong flywheel, which leads to more transactions,” adds Aggarwal, raising some red flags in terms of potential challenges. Its international business has been bleeding for a while. “Though the global market is a massive opportunity, the company has enough headroom for growth in India,” she says, adding that a focussed strategy always pays off in the long run. Another challenge for FirstCry is to migrate a chunk of population from unorganised to organised. “It needs to continuously add new users and upgrade the existing ones to premium products,” she further says.

Maheshwari, meanwhile, reckons he is not new to formidable challenges. The founder, who started his entrepreneurial innings in 2000 by co-founding edtech startup Brainvisa, takes us back to his first high and low in life. Though his first funding—₹1 crore—came quickly on the back of his B2C edtech plan, within six months he was staring at an uncertain future. “The dotcom bust happened, funding dried up, we couldn’t raise money, and were left with ₹40 lakh,” he recalls. The product was ready, but the market crashed. Along with his co-founders, Maheshwari made a quick pivot: From B2C to B2B. “We were forced to change the direction of the ship,” he says of his maiden venture that was acquired by Indecomm Global in 2007. “End of the day, it was a consulting business. It couldn’t scale,” he says.

Another challenge was controlling customer acquisition costs. “I realised quite early that business would never become sustainable if we didn’t fix CAC and logistics costs,” he says. The solution lay in building moats. “Moats never get formed by thoughts. They are built by execution,” he says, adding that FirstCry has been an execution machine. “Every successful venture in India is a story of execution. If one is good at it, execution eventually becomes your IP,” he says.

Maheshwari’s IP, interestingly, is not confined to just FirstCry. He is the man behind three unicorns: FirstCry, XpressBees, and GlobalBees. And he is still hungry for more and still has a firm eye on execution. “That’s how I am wired.”