Ashish Dhawan, Founder and trustee, CSF and Co-founder, Ashoka University

Ashish Dhawan, Founder and trustee, CSF and Co-founder, Ashoka University

Image: Amit Verma

Fifteen years ago, Ashish Dhawan, a private equity veteran in his mid-forties, decided to focus on tackling the education situation in the country through the non-profit route. His friends and colleagues found it difficult to believe that the co-founder of one of India’s first and most successful private equity funds, ChrysCapital, set up in 1999, could switch careers so abruptly.

Manisha Girotra, another industry veteran, believes Dhawan had a long runway of investing ahead of him. “He was regarded as one of the best brains in the financial services sector,” the Moelis India CEO recalls. “I also felt he was taking on a near-impossible task, and possibly setting himself up for failure, as no professional had ever dreamt of venturing into the education sector, let alone think of building a university.”

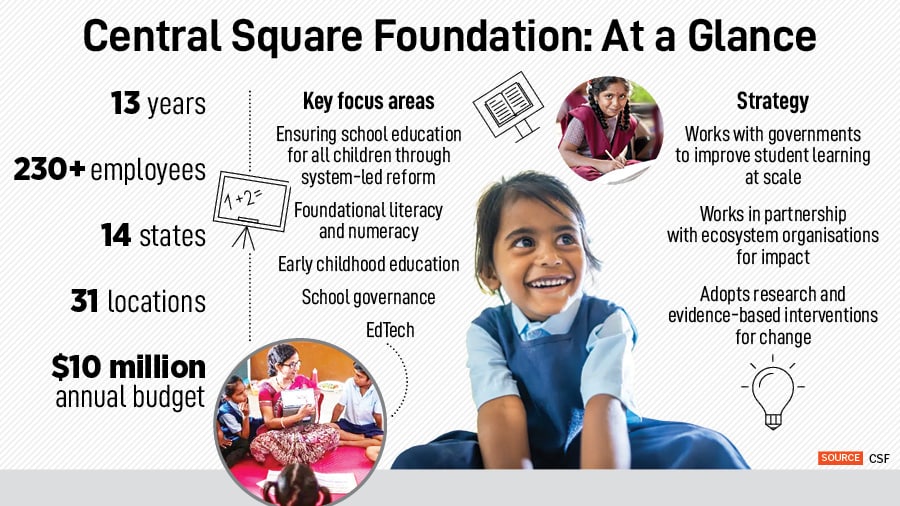

He established the Ashoka University in 2010 and the Central Square Foundation (CSF) in 2012 to stem the brain-drain the country had been grappling with. Through the Convergence Foundation, which he set up in 2021, his team has incubated more than 15 non-profit organisations that aim to address India’s biggest challenges.

“I didn’t want to just write cheques. My life’s work is about building institutions, as it was with ChrysCapital, which I built in the investing world. I am very proud of the fact that I have left and yet the institution continues,” Dhawan had said in an interview on Forbes India Pathbreakers in March 2023. “I feel that should be the mantra for everything. At the end of the day, whatever I build, I should eventually become redundant.” Forbes India also spoke with Dhawan on January 30 to discuss fresh developments.

“I didn’t want to just write cheques. My life’s work is about building institutions, as it was with ChrysCapital, which I built in the investing world. I am very proud of the fact that I have left and yet the institution continues,” Dhawan had said in an interview on Forbes India Pathbreakers in March 2023. “I feel that should be the mantra for everything. At the end of the day, whatever I build, I should eventually become redundant.” Forbes India also spoke with Dhawan on January 30 to discuss fresh developments.

Lightspeed India’s venture partner Vivek Gambhir says Dhawan was one of the sharpest minds at Harvard Business School, where the two were contemporaries. “Intensely focussed, deeply analytical, and always ready to push himself beyond limits. But what truly set him apart was his zest for life,” he says. “When he transitioned from private equity to the non-profit world, it was not just a career shift, it was a profound reimagining of how change could be created.”

When Dhawan left ChrysCapital, he did not have any more equity left in the firm, and he got off every corporate board. It was a signal that he was serious about his new career—that he was all-in.

However, transitioning from finance to philanthropy was anything but easy. Dhawan’s results-oriented, quick decision-making and sharp execution approach had to be adjusted to an environment where change is gradual. This called for a lot of patience. So he rolled up his sleeves and focussed on lasting, systemic change.

“Ashish has built institutions and movements that touch the lives of people across strata, across India,” says Amit Chandra, chairman, Bain Capital India.

Dhawan quickly realised that he would need to unlearn a lot from the world of business to work in the social sector. He understood that it would be impossible for any organisation to work in silos for long-term impact. Consequently, he brought together stakeholders, including governments, schools, non-profits, researchers, and the private sector.

Dhawan’s experience as a successful investor did come handy, though. “Ashish had one of the best qualities of an investor: His timing was impeccable, both at entry and at exit,” says Girotra. “You can punch him hard; he will come back stronger and more confident.”

Also see: Forbes India Leadership Awards 2025: An evening celebrating excellence in India Inc

The Birth of Ashoka

Sanjeev Bikhchandani, founder, Info Edge, remembers meeting Dhawan for the first time in 1999, when Dhawan had just founded ChrysCapital. “I went to discuss Naukri with him, but he preferred to invest in JobsAhead, which was founded by Puneet Dalmia and Alok Mittal,” Bikhchandani recalls. “But ties were formed there and then.” Naukri.com is the jobs listing website owned by Info Edge.

In 2006, Info Edge listed on Indian stock exchanges and in 2013 Monster bought JobsAhead for around `40 crore. Over the years, Dalmia, who had joined the family’s cement business and became managing director and CEO of Dalmia Bharat Group, became one of the founders of Ashoka University.

Bikhchandani, a St Stephen’s College alumnus, narrates how, in 2007, the alumni were discussing the wide difference in college admission cut-offs between the reserved and open categories. “Some of us started thinking of building a different kind of educational institution, one that would pursue both excellence and inclusiveness and with an interdisciplinary approach,” he recalls. “I discussed the idea with Ashish, and we went to Pramath [Sinha], who had the experience of building ISB, a unique management school,” he says. “Thus, the idea of Ashoka was born.” ISB is short for Indian School of Business, which has campuses in Hyderabad and Mohali.

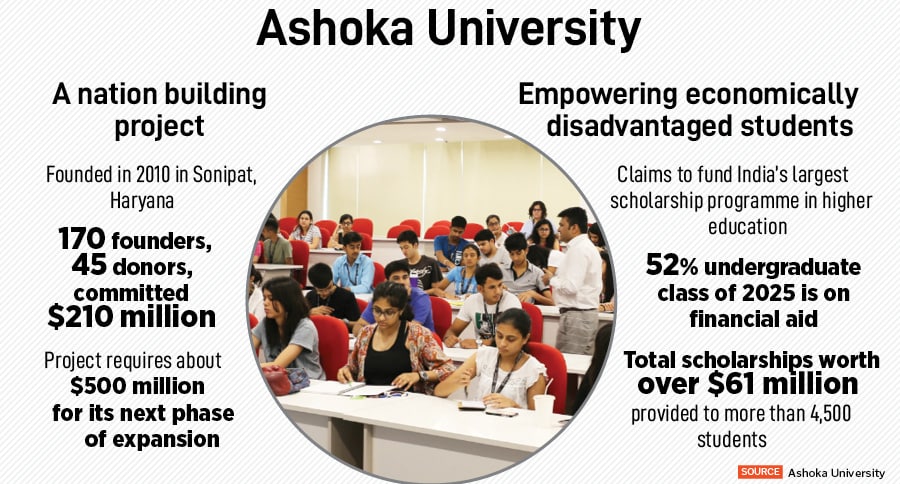

Dhawan got the ball rolling for a not-for-profit university built on the principles of collective public philanthropy to ensure an ethical and independent governance model for India’s first liberal arts and sciences university. He brought together 170 founders and 45 donors who collectively contributed `1,547 crore for the project. The foundation was laid in 2010.

The founders initially purchased 25 acres in Sonipat, Haryana, and inducted a base of 200 top-notch faculty members across major courses. Over the years, the management team has acquired more land and now owns around 93 acres. The university aims to expand its infrastructure, introduce new research and PhD programmes, and offer a wide range of courses that are in sync with technological disruptions in a rapidly changing world. Ashoka University claims to have the largest merit-based scholarship programme in India’s higher education system.

In the Forbes India Pathbreakers interview mentioned earlier, Dhawan explained how the nuances of establishing an education institute had to be very different from doing business. The idea was to have a shared governance model, and not to take funding from one family which would then become a dominant factor. Unlike businesses, “where you can start in a very scrappy manner and build something of quality later, in the [education] context you have to be world-class from day one,” he added.

He highlighted that people in the non-profit world were motivated differently from those in the corporate world, and that needed to be respected. “So, those are all new skill sets that I had to develop over time. And I actually enjoyed it because part of my heart was already there.”

Between 2022 and 2035, the founding team has earmarked `3,750 crore for long-term investments in critical areas. The vision is to institutionalise Ashoka and prioritise quality over growth. Dhawan and other founders want to commence the transition to a younger set of trustees and build robust frameworks. The founding team expects to build a reasonable corpus of endowment to ensure long-term sustainability.

“Ashish is probably the most successful philanthropist in India with a genuine passion for education and clarity of vision. His contribution in the field is tremendous,” says Bikhchandani.

Also see: Forbes India Entrepreneur of the Year: Supam Maheshwari and the FirstCry empire

Building strong foundations

Dhawan’s non-profit CSF focuses on improving the learning of school-going children through early childhood education reforms, and by strengthening school governance.

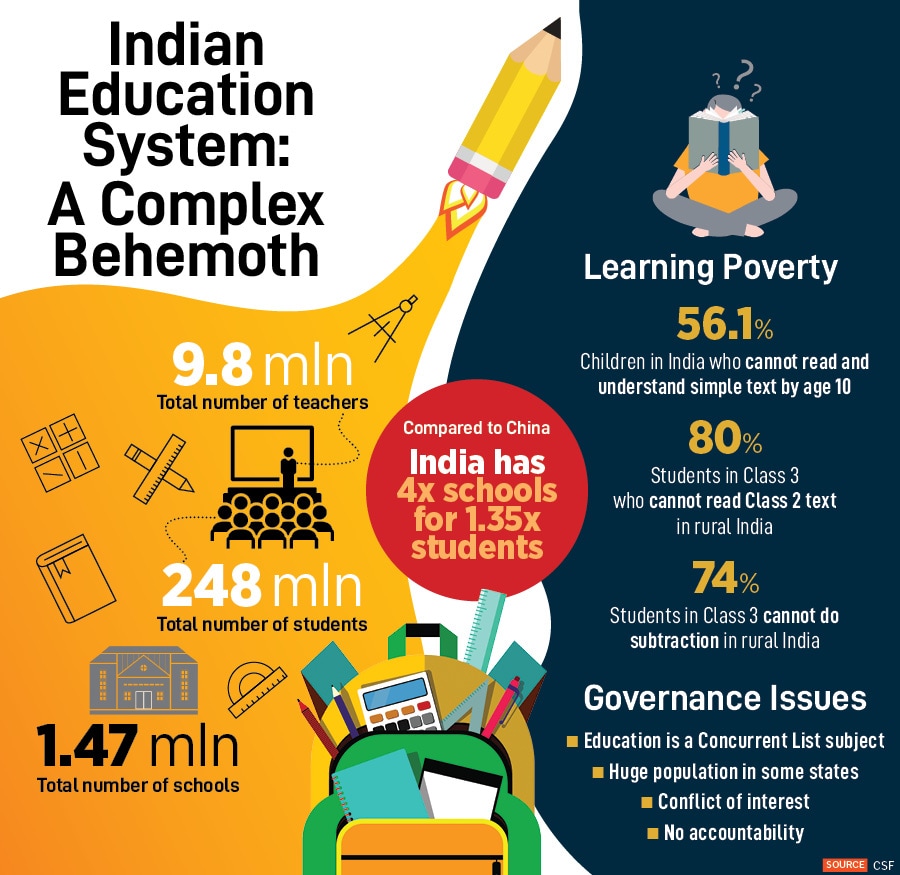

According to the World Bank Group, in 2022, 56.1 percent children in India at late primary age suffered from learning poverty, which is defined as being unable to read and understand a simple text by the age of 10. According to the Annual Status of Education Report (ASER) 2022, only 20.5 percent of Class 3 students could read a Class 2 level text, and only 25.9 percent could do simple subtraction. “Children start to fall behind early, by the end of Class 5, and if you can’t read by Class 5 you never catch up, and your learning trajectory plateaus,” says Dhawan.

Although the numbers have improved since 2018, ASER data shows children going to school does not necessarily mean they are learning.

“India has done remarkably well in terms of access. But we were struggling with learning outcomes, and frankly, learning outcomes only entered the vocabulary of the system in 2010,” Dhawan says. “Before that, it was all about access: How do we build more? How do we get more children to go to school? Do we hire more teachers?”

Dhawan explains that between the 1980s and 2010, the education system was focused on children gaining access to schools. But now nearly 98 percent of children in Classes 1 to 8 have access to schools. “The access problem in elementary school, which is primary-plus-middle, has been solved,” he says. “Children start dropping out in secondary school, but even that has improved. Now about 80 percent of children go to Classes 9 and 10, and almost 60 percent go to Classes 11 and 12.”

Since 2016 there has been a marked improvement in learning outcomes in several states. For example, says Dhawan, in Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, and Madhya Pradesh, which were lagging in learning levels, current outcomes have improved nearly four times in terms of the percentage of Class 5 students who can read and comprehend basic text, and do additions and subtractions.

“What I admire most about Ashish is his commitment to large-scale, systemic change. Many of us dream of making a difference in one or two areas of life, but for Ashish, it is an ongoing, never-ending pursuit,” Gambhir says. “Through CSF, he did not just fund projects; he built ecosystems, brought together policymakers, educators, and philanthropists, and created a movement for education reform.”

Gambhir, who is on the CSF advisory board, has closely seen how strategically Dhawan has leveraged the power of data, research, and innovation to help the foundation become a powerful catalyst for enabling change. “Whether it is working on foundational literacy, improving teacher effectiveness, or influencing government policy, Ashish has ensured that CSF is not just a funder, but an enabler for systemic impact,” he adds. “The ability to bring together stakeholders—often with differing priorities—and align them toward a common vision of quality education for all is what makes his approach truly commendable.”

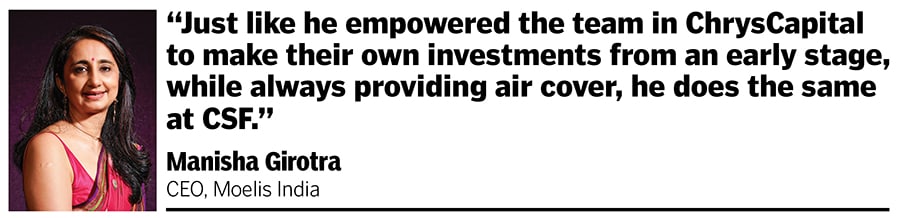

Girotra, who is also on the CSF advisory board, adds that Dhawan has carried his style of investing and doing business into the world of philanthropy. “Just like he empowered the team in ChrysCapital to make their own investments from an early stage, while always providing air cover, he does the same at CSF,” she remarks. “He has encouraged and pushed the team to push the cause with governments, donors, and other stakeholders independently, but is always a call away if they need his help.”

Gambhir describes Dhawan as someone who embodies the “work hard, play hard” attitude. “I vividly remember that at any party, while most of us would be winding down, Ashish would be the last person standing—energising everyone, keeping the conversations going, and ensuring no one left without a great time,” he says, adding that he has the rare ability to be both deeply serious and incredibly fun-loving at the same time.

“It is no surprise that his journey has been one of transformation, not just for himself, but for everyone around him,” Gambhir says.