Bugworks Research co-founders (from left): Balasubramanian Venkataraman, Anand Anandkumar and Santanu Datta. Image: Nishant Ratnakar for Forbes India

Bugworks Research co-founders (from left): Balasubramanian Venkataraman, Anand Anandkumar and Santanu Datta. Image: Nishant Ratnakar for Forbes India

Bugworks Research, as the name suggests, is home to scientists working on drugs to combat microbes such as bacteria that cause a variety of infections. What makes Bugworks stand out is that the venture is working to bring to market a novel class of antibiotics to combat the rise of bacterial resistance to existing medicines. It is also using some of the same knowhow to develop cancer drugs.

Bacteria can change themselves, some in a matter of hours, and this way they develop resistance to medicines such as antibiotics. Even with treatable everyday infections, the bugs are becoming more resistant and the risk of available medicines not keeping up is increasing.

Scientists call bacteria becoming resistant to a range of medicines ‘multi-drug resistance’ or MDR, and the resulting problem in treating infections is recognised by the World Health Organization (WHO) as ‘antimicrobial resistance’ or AMR.

“This year could be crucial for us. If things go well, we would have three phase-I [trials],” says Balasubramanian Venkataraman, co-founder and COO of Bugworks. Two of those are in the area of AMR—one is to test intravenous injections and the other an oral version. The third is an early-stage molecule that is showing promise as a cancer drug.

On the AMR front, “we have a product bubbling up to the top because it’s broad spectrum, it handles ‘Gram negatives’, ‘Gram positives’, and bioterrorism pathogens,” says Anand Anandkumar, co-founder and CEO of the company. (Gram negative and Gram positive refer to a staining test that reveal the category of the bacteria, which, in turn, is related to the structure of its cell wall).

Anandkumar founded Bugworks in 2014 in the US and India, alongside Santanu Datta, who is now a mentor at Bugworks, and Balasubramanian. Shahul Hameed, chief scientific officer, is the fourth member of the founding team. Today the venture also operates out of Australia, where it is running the phase-I trials.

Like in any drug discovery process, testing this first molecule against MDR, which has initially been named BWC0977, has also not been without difficulties. For example, some blood clotting was found when tested in two healthy volunteers as part of phase-I trials of the intravenous version. Other tests included figuring out if the molecule had any effect on the rhythm of the heart.

Meanwhile, work on the oral version has caught up, Anandkumar says. “So if everything aligns, we could have IV (intravenous) and oral going through phase-I in AMR, and our lead asset in immuno-oncology will also enter phase-I,” he says.

Also read: Fighting Superbugs: How an Indian Avenger is building a life-saving weapon

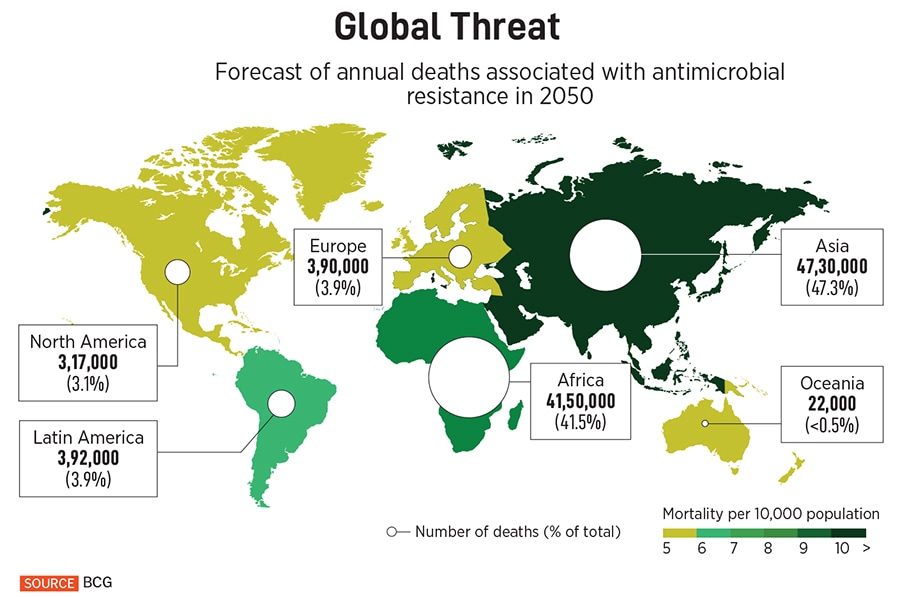

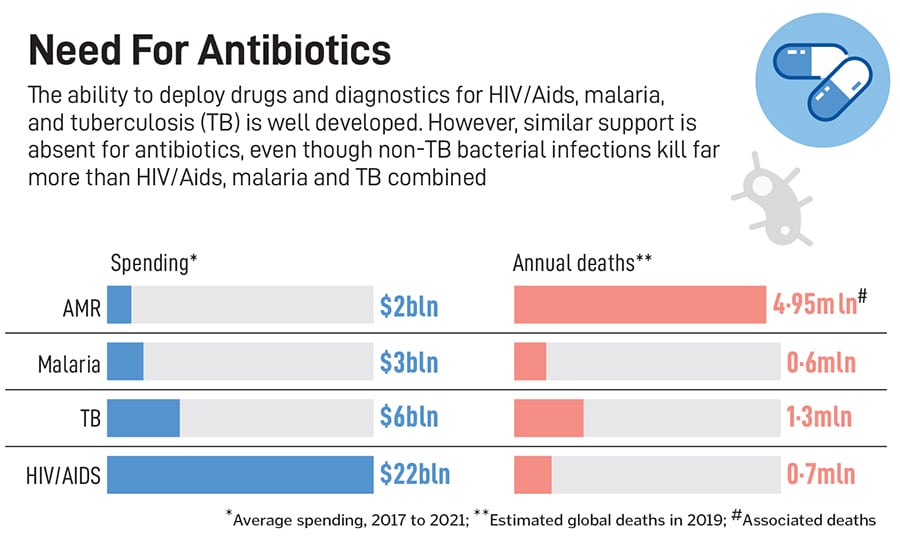

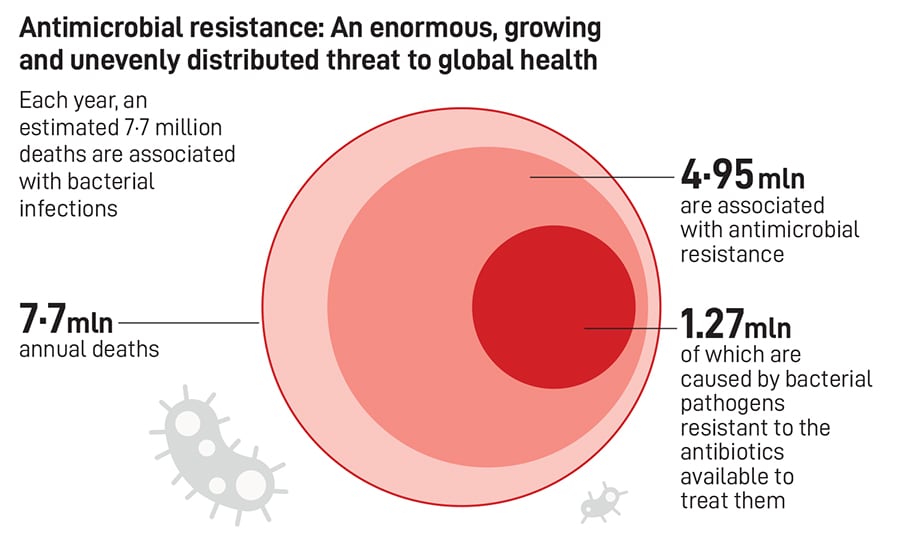

Since the introduction of fluoroquinolones (FQs) in the 1980s, there has not been a broad-spectrum class of drugs that is effective against multiple pathogenic bacteria, Hameed and fellow researchers at Bugworks write in a paper published in the scientific journal Nature Communications in September 2024. They note that bacteria becoming resistant to a range of medicines, or MDR, has caused 4.95 million deaths in 2019, with a disproportionate impact on low and middle-income countries. They also write that the WHO counts antimicrobial resistance among its top ten global public health threats, and quote a 2022 report by the consultancy Boston Consulting Group, which projects some 10 million AMR deaths by 2050.

Recounting the technical aspects of the progress they have made on AMR in the paper, Hameed and the others explain how their tests thus far show BWC0977 “demonstrates broad-spectrum activity against the major WHO published list of ‘global priority’ pathogens”, including some that are resistant to carbapenems [a class of antibiotics used to treat serious bacterial infections].

Balasubramanian hopes that by mid-to-late 2026, they should have completed phase I.

“Our initial thinking was that their AMR drug has a huge opportunity to be the best drug in the global South,” says Kiran Mysore, a principalat the University of Tokyo Edge Capital (UTEC), a leading venture capital investor in deep science around the world. “But they have emerged as one of the very few such companies according to the WHO, with both IV and oral, and a novel broad-spectrum across the world.”

Listen: Anand Anandkumar at Bugworks on how India could become a powerhouse of biotech research

UTEC led Bugworks’s Series A $9 million funding in 2018, with participation from 3One4 Capital and a couple of angel investors. The following year, UTEC also announced a partnership with Blume Ventures called BUDHA (Blume UTEC Deep-tecH Accelerator) to back promising deep science ventures in India.

Mysore recalls, “On my first day at work at UTEC, I got in touch with Bugworks, and they were my second investment in India.” He had walked into a conference organised by Carnegie Endowment’s Indian unit, thinking it would be unlikely he would run into any exciting prospects at a policy-focussed meetup, until he heard Anandkumar talk about Bugworks. It was Mysore and UTEC that introduced Bugworks’s founders to a reputed Japanese microbiologist, professor Murakami, who had done pathbreaking work on how bacteria push medicines out of their bodies.

This helped Bugworks develop the way in which BWC0977 tackles a bug. The company has found a way to attack bacteria in two places at once, hitting two enzymes needed for the bug to multiply and thrive—and the method has been found to be efficacious across different types of bacteria.

One important way the microbe defends itself is called an ‘efflux pump’ that throws out the medicine that could have fought it. Instead of tackling the pump directly, Bugworks has found a way to make their drug invisible to it. This combined strategy of targeting the bacteria at two places, and also fooling the efflux pump mechanism, has given Bugworks a new antibiotic.

The global collaborations from Japan, the US, Europe, Australia and South Africa are an important reason for Bugworks having come this far, Mysore says. “They’ve combined this attitude of innovation inside and execution outside,” he adds.

What will be crucial to Bugworks’s commercial success, eventually, is that “it is the only company in our life sciences portfolio that has both the people from global South as well as from the OECD countries who are invested in it in multiple forms”, Mysore explains. It means it has stakeholders who will help take the drug to both the rich countries, with the IV formulation, which is “high value”, but also the oral version, which is a “high need” in the emerging markets.

Mysore also says that Bugworks is “not a one-trick pony” and that their platform approach is allowing them to build not just one product but a pipeline, which is crucial to a drug company’s long-term success.

Also read: New lease of lifetech

One important reason the founders of Bugworks are optimistic about the prospects of their venture is that they have built a platform that can generate multiple leads. The platform is called GYROX, the name inspired by Gyrase, an enzyme crucial to DNA replication. Even if, for instance, BWC0977 does not make the cut, eventually, there will still be other leas in the pipeline, generated by GYROX.

Therefore, following phase-I, there is an opportunity to both partner global companies or “maybe we could take it all the way ourselves”, Anandkumar says. If there is a lead asset and the prospect of a pipeline of future generations of the drug, there will be a chance to build a franchise for the next half a century, he says.

In the case of the cancer molecule, a successful phase-I could lead to a partnership with a large multinational drug company, because such drugs are prohibitively expensive for small startups—typically costing hundreds of millions of dollars to conclude phase three trials. That is why the next 12 to 18 months are going to be crucial for Bugworks.

Datta adds that Bugworks has also established partnerships with hospitals in Bengaluru. For example, they have collaborated with St John’s Medical College Hospital and Narayana Health to get bacteria samples on which to test BWC0977. “We tested our molecule taking the worst bacteria from the local ecosystem, so it could withstand the worst in the world,” he says. For their immuno-oncology pipeline, they collaborated with Cytecare Hospital, where Bugworks opened a research lab in September 2022. At the lab, Bugworks is able to test its molecules on post-surgical fresh tissue.

Before Bugworks, Anandkumar, who has a PhD in electrical and biomedical engineering and chip design, had worked for some 15 years in the semiconductor industry in the US, Europe and Japan. Back to India in early 2000s, he ran the Indian operations of Magma Design Automation, a fabless chip design company that was acquired by Synopsys. It was a personal health crisis that turned his attention to biopharma.

He founded Cellworks in 2007, collaborating with friends in the San Francisco Bay Area and Bengaluru, which provides a simulation platform used by hospitals in the US to customise treatment for cancer patients not responding to first-line treatment. Bugworks was spun out of Cellworks in 2014.

He founded Cellworks in 2007, collaborating with friends in the San Francisco Bay Area and Bengaluru, which provides a simulation platform used by hospitals in the US to customise treatment for cancer patients not responding to first-line treatment. Bugworks was spun out of Cellworks in 2014.

Anandkumar’s encounter with his co-founders and the subsequent founding of Bugworks was serendipitous. Datta, Balasubramanian and Hameed were experienced researchers at Avishkar, AstraZeneca’s infectious diseases R&D centre in Bengaluru, when Anandkumar cold-called their then-boss TS Balganesh to see if Cellworks could collaborate.

When AstraZeneca decided to shut down Avishkar in 2014, all of them decided they could go from researching medicines for tuberculosis to fighting MDR superbugs, and thus was born Bugworks. Many others on Bugworks’s 35-person team are ex-AstraZeneca.

In India, the abuse of antibiotics is rampant. Even in the big cities, it is common for people to approach pharmacies and buy a strip of some antibiotic or the other based on the pharmacists’ advice—a practice that is far cheaper and more convenient than finding a good doctor, even if potentially dangerous. Further, we also find antibiotics coursing through our food supply, given their indiscriminate use in poultry farming and cattle rearing.

That apart, nearly a third of the deaths in hospitals in India, when people visit for surgical procedures, for instance, is due to hospital-acquired infections of bacteria that are drug-resistant. Bacteria can double every 20 t0 30 minutes, which means that in a day, one bug can go to a billion and make the infection acute in a couple of days.

The problem of AMR is also exacerbated by the absence of serious interest in it from the world’s biggest drug companies. Medicines for AMR are deployed only as a last-line-of-defence. Therefore, they are generally not mass-market ones. They are made in smaller quantities and have to be sold at high prices.

Among the larger companies looking to commercialise AMR medicines is GlaxoSmithKline, which has completed three phase-II trials for its drug called Gepotidacin to treat urinary tract infections and gonorrhoea.

Zoliflodacin, an oral drug developed by Entasis Therapeutics, a US-based biopharma startup that was acquired by a holding company Innoviva in 2022, has completed a phase-III trial in treating urogenital bacterial infections.

Among India’s established biopharma companies, Enmetazobactam, an injectable drug developed by Orchid Pharma, is the first antimicrobial from India approved by the US Food and Drug Administration, according to a December 2024 BBC report. At Wockhardt, Zaynich, a new antibiotic for severe drug-resistant infections, is in phase-III trials. Wockhardt is also testing Nafithromycin, in phase-III trials as an oral treatment for pneumonia, with commercial launch expected by late this year, according to the BBC report.

When it comes to profiting from AMR medicines, they are nothing like the ‘blockbuster’ multi-billion-dollar drugs developed to treat cancer or heart disease or even mental health-related medicines.

Therefore, public-private partnerships have largely driven the funding of ventures such as Bugworks. Specifically in their case, Bugworks has struck international partnerships, including with the non-profits CARB-X (Combating Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria Biopharmaceutical Accelerator) and GARDP (Global Antibiotic Research and Development Partnership).

If phase-I, which includes healthy volunteers, goes through, then at phase-II, Bugworks has selected urinary tract infection as the first problem to tackle and tests will be done with around 200 people, including patients. Phase-III will involve about 2,000 patients. Overall, it is a five- to six-year slog ahead for Bugworks before it can see its AMR drug in the market.

Bugworks has raised about $8 million in grant money mostly from CARB-X, but also small contributions from India’s department of biotechnology and other organisations. It has raised about $35 million in venture capital funding, from backers, including Lightrock India, 3one4 Capital, Global Brain, UTEC, and Acquipharma Holdings, through Series B investments. The founders are deep in talks to raise a much larger Series C round, which would keep them going through at least their phase-II trials.

“We’re talking to global funds. And we are hopeful that this year will be fantastically inflective both on the science, the phase-I completion, and having significant funding,” Anandkumar says.