Riyaaz Amlani, Founder & MD, Impresario Entertainment & Hospitality Pvt. Ltd. Image: Neha Mithbawkar for Forbes India.

Riyaaz Amlani, Founder & MD, Impresario Entertainment & Hospitality Pvt. Ltd. Image: Neha Mithbawkar for Forbes India.

Riyaaz Amlani has a penchant for conversations. Seated at the Khar Social in Mumbai to talk about the mechanics of scaling up restaurants, he seamlessly segues into discussing Mumbai’s dug-up roads, post-Halloween decorations hanging from the ceiling or the intuitiveness of modern transcription software—“Those [the software] must have made your lives easier, no?” he asks.

Perhaps no surprises that the nearly-Rs 600 crore F&B empire that Amlani has built in just under a quarter of a century is hinged on a simple premise: Of creating spaces that foster conversations.

In 2002, Amlani, the CEO and founder of Impresario Entertainment and Hospitality Pvt ltd, had set up his maiden venture with Mocha, a cafe styled on the Moroccan qahwah khannas, on the porch of Berry’s, a restaurant run by his father on Mumbai’s Churchgate Street. Much before the coffee culture caught on in India and at a time when cafes were confined to the swanky interiors of 5-star hotels, Mocha served up not only 22 varieties of beans but also a “third place”—what former Starbucks CEO Howard Schultz had envisioned his multinational coffee chain to be—a hangout spot outside of homes and offices.

Amlani’s F&B portfolio has only expanded since: Besides Mocha, he has successful standalone restaurants like Saltwater Cafe (now rebranded into Bandra Born) and Smoke House Deli, Michelin-starred chef Garima Arora’s first India venture Banng, the European-themed Slink & Bardot, and a few now-shuttered iterations (French bistro Soufflé S’il Vous Plaît or marketplace Flea Bazaar Cafe).

Also read: Delivery and revenge dining: How Riyaaz Amlani survived the Covid-19 battering

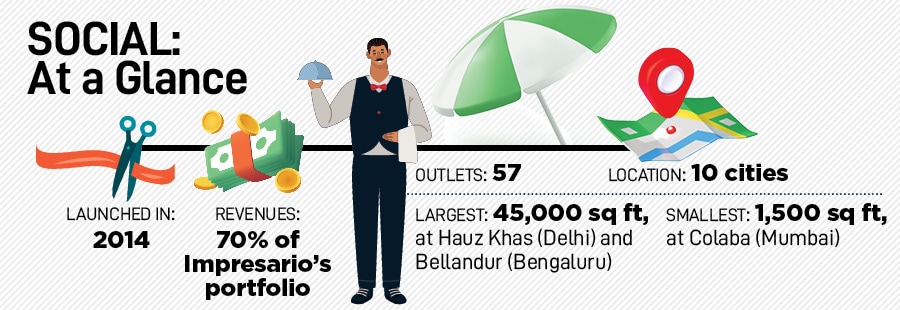

But it was in 2014 that he found his El Dorado in Social, a property that was fashioned as a casual dining space where people could hang out and also work from—the fourth place, if you will. The proof of the pudding lies in Impresario’s FY24 turnover of Rs 579.95 crore, a 9x-plus rise in the Rs 62 crore topline it clocked in FY14, the year Social was launched on Bengaluru’s Church Street (according to financials sourced from Tofler). During this period, the restaurant has grown to 57 outlets across 10 cities bringing in 70 percent of the revenues for a group that houses eight brick-and-mortar and three cloud kitchen brands. It also comprises a lion’s share of the 65-plus outlets that Impresario operates overall—effectively, nine out of 10 Impresario restaurants is a Social.

“The time we launched Social was also the time when the internet companies were coming back, hustling was in, and the sharing and the gig economies were growing,” says Amlani. “We realised people needed a space where they could work and also hang out to network socially. That was a light-bulb moment for us.” With workspaces on offer, Social was conceived to bridge a gap in the F&B formats, enabling a customer to finish a cup of coffee, yet hang back without ordering the extra muffin or a guilt trip.

For Rs 300 a day, Rs 1,200 a week or Rs 4,500 a month, Social offers free WiFi and a dedicated workspace, enabling many startups to work from the restaurants before their toplines afford them the luxury of a permanent office. At Delhi’s Hauz Khaz outpost, Aman Gupta, co-founder of boAt, started his venture, while Amit Doshi, head of IVM Podcasts, Pratilipi, launched his from Khar Social. “While we were working there, we connected with a number of entrepreneurs who we are still in touch with. That ability to network was a big unanticipated benefit,” says Doshi.

The sweet spot

Social’s expansion comes at a time when India’s organised food services space, while growing at a fast clip—a CAGR of 13.2 percent to reach a market share of 52.9 percent by 2028, according to a report by the National Restaurant Association of India (NRAI)—is confronted by a question of longevity. Sagar Daryani, founder of Wow! Momo and president of NRAI, recently told the Economic Times that at least 30 to 35 percent of mid-sized restaurants and cloud kitchens have shut down in the last one and a half to two years, while pubs and smaller casual dining restaurants (CDRs) are also facing closure due to higher operational costs.

Also read: Aditi Dugar: Cooking up a storm

Amlani, though, bets on the sweet spot that Social has hit in terms of the average per cover (APC), a key metric to assess restaurant performance. The chain’s APC is around Rs 900, far north of the Rs 300 for cafes like Mocha, but way below Rs 2,000 for the fine-dining restaurants in Impresario’s portfolio. With the sizes of Social outlets ranging from 1,500 sq ft (in Mumbai’s Colaba) to 45,000 sq ft (in Hauz Khas and Bengaluru’s Bellandur), the restaurants service between 70 and 500 covers a day depending on their location.

“The entire business of restauranting, in a nutshell, is about being able to turn tables around. In Mocha, we had 500 people per store per day, but with a lower average spend, while our fine-dining restaurants would have far higher spends but only 100 covers a day,” says Amlani. “We were trying to find a format with the right kind of pricing that would help us maximise APC. With Social, we found the right product-market fit.”

Samir Kuckreja, founder and CEO of Tasanaya Hospitality, a boutique consulting firm, agrees: “I recently read that about 40 percent of restaurants in India shut within the first 12 months. Social is an outlier, which has successfully operated for over 10 years.” Kuckreja was formerly the CEO and MD of Nirula’s Corner House and the Joint MD of Yum Restaurants that runs Pizza Hut and KFC in India.

One of the strategies to maximise its earning potential has been to sweat the property across demographics—as a workspace-cum-restaurant during the day, and a pub in the evening to cash in on the post-7 pm footfall. “They have my business during the day, where I meet people over lunch, and they have my daughters’ business in the evening. It is one of the first brands I have seen target multiple customer segments at different times of the day. They have pivoted multiple times to keep the brand relevant. Few brands have that agility.” says Kuckreja.

A lever to appeal across demographics, and entice a different kind of hanging out, was the launch of antiSocial in 2016, a performing arena to platform experimental art and artistes—from live music to rap battles to the spoken word. Why would a restaurant craft an alter ego that had nothing to do with restauranting? “To go a little off-centre,” says Amlani. “Social is slightly more embracing, while antiSocial is very specifically underground, emerging culture.” It may sound counter-intuitive, but Amlani insists it’s tied to the theme of inclusivity he has been trying to manifest through this property. He recalls how a Divine concert at Khar Social in its early years had turned into a confluence of visitors from Dharavi, Asia’s largest slum, and Mumbai’s tony Bandra neighbourhood. “It validated our thoughts,” he says. “For us, the intention has always been to have a mass appeal, yet do something edgy, aspirational.”

Also read: What makes legacy brands stay relevant despite changing tastes

Accessibility is a leitmotif Amlani retains across Socials. “We’ve created it to feel like an old shoe, where you can be comfortable and make the conversation your highlight,” he says. The menu is common across all outlets, and is a mixed bag inspired by the social spaces of the country—the chaai tapris, railway kitchens, college canteens, what have you—bridging the India vs Bharat divide. “You may want eggs and baked beans for your breakfast, but you may equally want poori-aloo or idli-dosa. The idea is to have something for everyone,” he adds.

Social at Hazratganj, Lucknow.

Social at Hazratganj, Lucknow.

Essentially, Social has eliminated the intimidation that comes with restaurants. “It has struck a balance between the ‘theka’ and the gentrified places. A guy like me, who has studied in a Hindi-medium school, would typically be scared of walking into these restaurants in Delhi or Mumbai. Social has broken that barrier,” says chef Manish Mehrotra, who, till recently, was the culinary director of Indian Accent, one out of the only two Indian restaurants in the top 100 of The World’s 50 Best Restaurants list.

The move beyond

With consumption in tier 2 cities surging, Social is now foraying beyond metros, opening five outlets across four locations—Dehradun, Indore, Lucknow and two in Chandigarh. According to a July 2024 report, How India Eats, co-authored by Bain & Company and Swiggy, while 70 percent of the food services consumption in 2023 is concentrated in the top 50 cities and will continue to be so, incremental growth is expected to come from tier 2 cities and beyond. “The cultural aspect of how often you go out is different in tier 2 cities. But now, there is a slow shift,” says Amlani. “When we did the Korean festival with authentic Korean food, it had greater traction in outlets like Dehradun and Thane (Mumbai’s neighbouring district) than in the posher Bandra and Colaba neighbourhoods [of Mumbai].”

In 2022, India Resurgence Fund (India RF), a joint venture between Piramal Enterprises and Bain Capital, invested Rs 550 crore in Impresario, Social’s parent company, becoming its majority shareholder. According to media reports, it is the single-largest private equity deal in India in the CDR segment. The deal led to the exit of L Catterton Asia, a global private equity firm backed by luxury company LVMH, which, in 2017, had invested Rs 100 crore for a 70 percent stake.

The magnum deal sizes would have vindicated Amlani’s conviction in a brand that was once vehemently opposed by his board. “I told him it won’t work. India just wasn’t ready for it,” Deepak Shahdadpuri, the first external investor for Impresario in 2008 (as part of the Beacon India Private Equity Fund), had told Forbes India in an earlier interview. “He insisted this was a product that will survive for the next 10 years.”

Bellandur Social in Bangalore.

Bellandur Social in Bangalore.

Not only has the brand survived but has also brought in funding for the parent company. “The bet was on scaling Social on both of the funding rounds [L Catterton Asia and IndiaRF],” says Siddharth Bafna, partner and head-corporate finance, Lodha & Co, the financial advisors for both the fundraises. “The company does have brands like Slink & Bardot, Smoke House and Banng, but the real thesis behind both those investments was really the scalability of Social as a brand.”

“I don’t think you can count more than 2-3 entities in the Indian casual dining space in the bracket of $100 million, give or take,” adds Bafna. “One is Barbeque Nation, the other is Impresario. I struggle to think of a third. I think in Riyaaz the investors saw someone who had the ability to build an organisation and had the systems and processes to scale a business.”

With fresh infusion of capital, Amlani now wishes to expand Social further, at the rate of 12 outlets or so a year. His eventual target is to reach 100, but he won’t commit to a timeline. “I would love to set a target for you, but no. We make a plan one year forward and we stick to that,” he says.

At 16, Amlani got thrown out of school for trying to sell marbles to kids. At 50, he’s minted millions by selling the idea of a conversation.