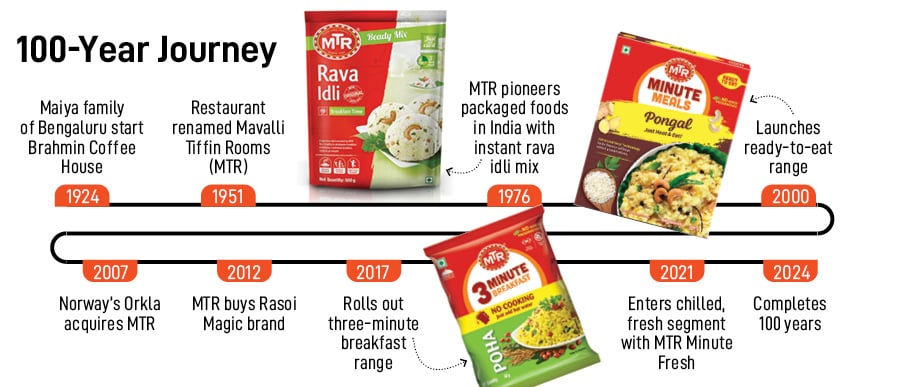

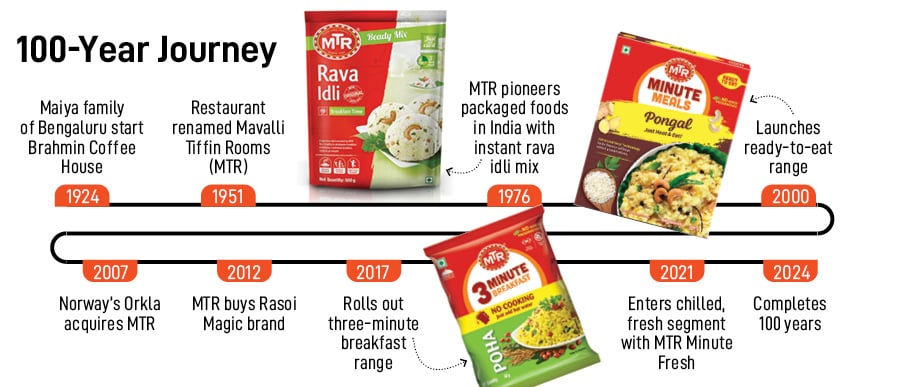

The celebrations, though, were not restricted to Bhasin and thousands of food lovers. A heritage food brand was also celebrating the state’s rich culinary heritage. “MTR Karunadu Swada is born out of MTR’s love for the food and culture of Karnataka,” says Bhasin, chief executive officer of MTR, a 100-year-old company that traces its roots to 1924 when Brahmin Coffee House was started by Bengaluru’s Maiya family. The restaurant was renamed Mavalli Tiffin Rooms (MTR) in 1951. Over half a century later, MTR was bought by Norwegian conglomerate Orkla in 2007. “We have been a champion of local brands,” says Bhasin, who joined MTR as chief marketing officer in 2016. Five years later, he became chief commercial officer. Karunadu Swada, he underlines, is Orkla’s commitment to upholding Karnataka’s rich culinary heritage.

The food festival, Bhasin adds, serves as a bridge back to the cultural roots of the state. With evolving consumer needs and fast-paced lifestyles, people have inadvertently lost touch with traditional recipes and flavours. The chefs use locally sourced ingredients, unique spice blends, and recipes passed on through generations. “This festival is an effort to preserve a piece of the Karunadu heritage through these treasured dishes,” says the CEO, who asserts that MTR has become an integral part of the cultural fabric of the state over the last century.

Sanjay Sharma, CEO of Orkla India, explains why Orkla decided to play the ‘vocal for local’ game with MTR. When the Indian brand was acquired in 2007, Orkla found itself shouldering big responsibilities. The first was to stay true to its consumers. “MTR evokes strong emotions in Karnataka and resonates deeply with the consumers,” says Sharma, who joined Orkla in 2009 and played a key role in ensuring a smooth brand transition from a local owner to a global company. MTR defined the food culture of Karnataka. So, Orkla needed to remain the cultural champion of the brand. “Imagine a Punjabi heading a 99 percent Kannadiga business,” says Sharma, alluding to the rich diversity of the country and the brand.

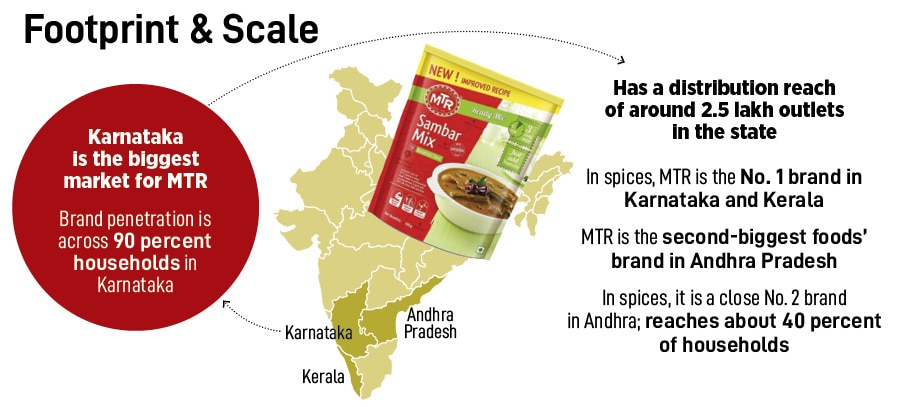

The second responsibility was to ensure that MTR remained focussed on its core state: Karnataka. In 2009, MTR was available across the country. “It had a large footprint,” recounts Sharma, adding that one of the first tasks he undertook was pulling back the footprint of the brand. There were three reasons. First, the processed food market was largely confined to the top 50 cities of the country. “There was no point in taking our resources and going to 150 or 200 towns across India,” he says. “So, I decided to pull it back.” Second, there are two ways to grow any consumer brand: Go horizontal, which means expanding the footprint across the states or go vertical, which means going deep into a state.

Back in 2007, Karnataka estimated to account for over 90 percent of MTR’s sales. “So, we decided to go deep into our geography and unlock new territories,” he says. Lastly, shunning a pan-India strategy gelled with Orkla’s DNA. “We believe in buying and building local brands,” he says. When Orkla bought MTR, it did not see a national business. “We saw a flourishing regional business in it,” he says. “We don’t want to be a small fish in a big pond, but a big fish in a small pond,” says Sharma, adding that the strategy to remain local also made sense on another count. “Food is local,” he says, smiling.

Also read: What makes legacy brands stay relevant despite changing tastes

MTR 2.0 meant more of Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, and a new game plan. Sharma rejigged MTR’s product portfolio as well. He pulled the plug on the ice cream business. “It was doing well, but was a low-margin and low-turnover business,” he says. But the size was not the deciding factor in exiting the vertical. “It was not the core of MTR,” he says. MTR used to have a snacks vertical as well. “We realised it’s a low-margin business, and not the core. So, we exited that too,” he says.

Another change cemented an emotional bonding with the employees. Sharma roped in functional experts and infused competencies. The reason? Entrepreneur-run organisations tend to give more weightage to loyalty than to competence because all the entrepreneur wants are trusted people who would execute his command. “We made people believe that they could run the business,” he says. The new owner also beefed up consumer insights behind the brand. “We contemporised the brand, launched it with new packaging, identity, and a new theme,” he says. The advertising spend was increased from 5 to 6 percent of sales to 14 percent.

Also read: MTR Foods fires first salvo in the battle of the batters

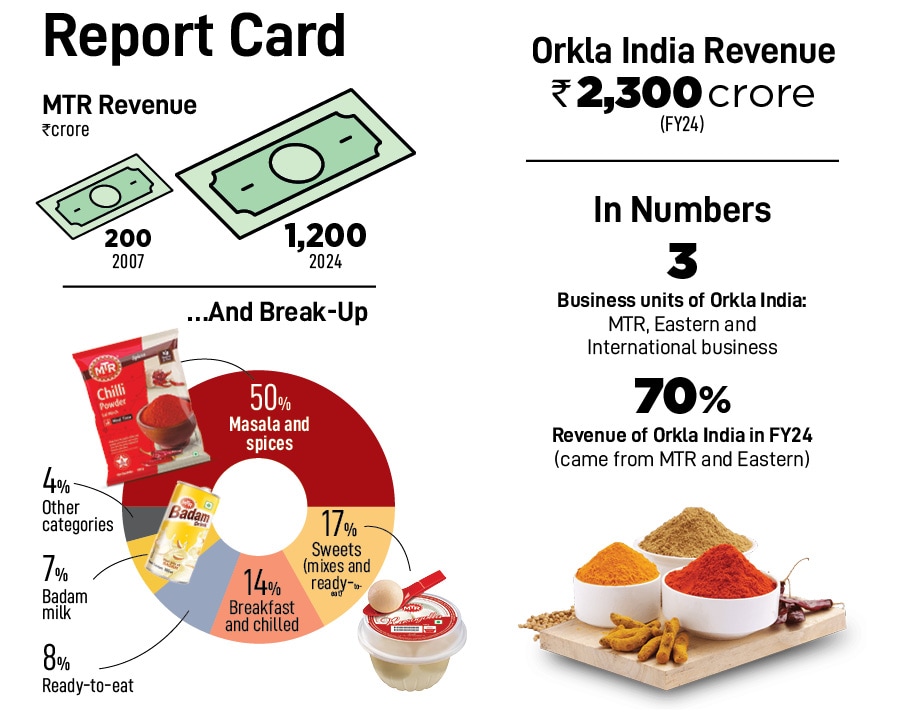

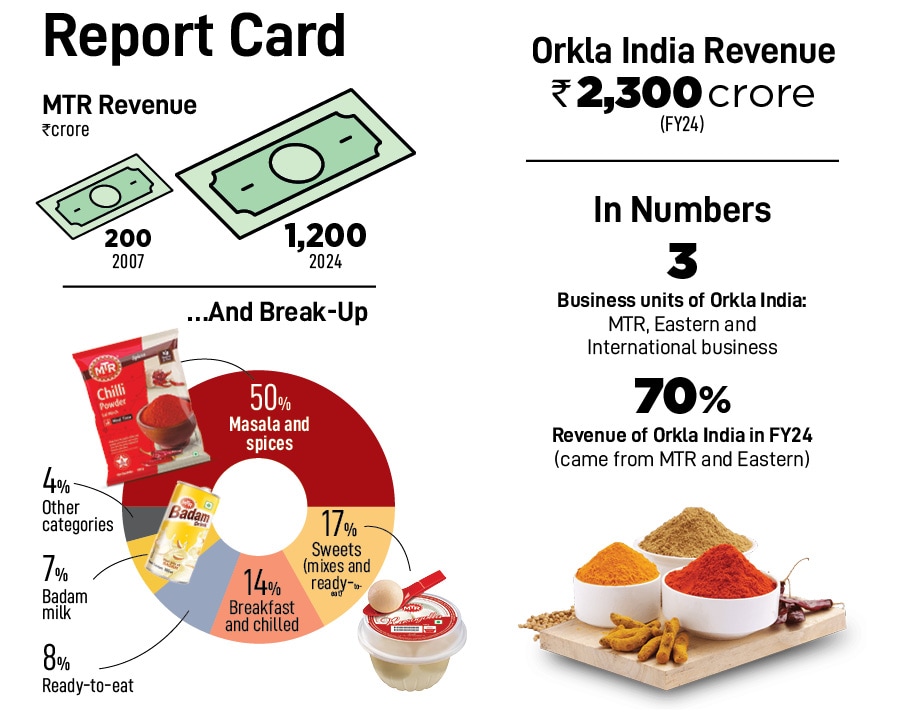

The gambit seems to have paid off. A 100-year-old brand has grown from Rs200 crore to Rs1,200 crore in revenue, and is still going strong. So, what is MTR’s secret sauce? Bhasin reckons it’s a no-brainer. The brand stayed rooted to its core and history. The only change, he underscores, has been in embracing change. “We are still rooted in culture, but we are contemporary. And that’s also the reason why we have been able to survive and thrive,” he says.

The success of MTR, reckon brand and marketing analysts, also redefines the story of David and Goliath, where the former eventually morphs into the latter. “In the beginning, every brand is small,” says Harish Bijoor, who runs an eponymous brand consulting firm. Every brand starts as a thought—call it dry seeds—that gets the right kind of backing and effort, he says. And what makes it big? A good product, a great price, well-oiled distribution, a savvy brand, and an excellent set of people. “When I look at regional brands, every effort has been an effort of involved passion,” he says, adding that behind every big brand, there is a passionate entrepreneur. Take, for instance, Haldiram’s ‘bhujiya’ from Nagpur, ‘kadak’ Gujarati tulsi tea, Bhima Jewels of Kochi, and Walkaroo sandals from Coimbatore. In many ways, each of them was once a David, which turned into a Goliath.

Listen: What makes a brand a Regional Goliath?

There are undoubtedly pluses of harbouring pan-India aspirations, but the arguments for shunning such a route are equally compelling. “Look at Mother Dairy. It’s a Delhi-NCR brand and still rules the roost despite phases of losing intensity and market share for a while,” says Ashita Aggarwal, professor (marketing), SP Jain Institute of Management and Research. Then there is Wagh Bakri tea, which still dominates in Gujarat. In 2022, Karnataka’s population, she underlines, was estimated to be equal to the UK. The point is that the Indian states are bigger in size and population compared to most of the European countries. “So, what would you do? Rule a state which is almost like a country or run after other states?” she asks, adding that it makes ample sense to go an inch wide and mile deep.

Bhasin too swears by the ‘vocal for local’ mantra. The brand reflects the ideology in its products and commercials. Recently, MTR rolled out a TV campaign for puliogare powder—a spice blend that primarily uses tamarind, red chilies, and other spices to create a popular dish called puliogare. The commercial, Bhasin says, captures the heart of Karnataka’s rich culture through the story of a young boy mastering the art of Yakshagana. “It’s a harmonious blend of tradition, emotion and flavour,” he contends.

The challenge, though, for MTR is quintessentially what every regional Goliath faces at some point in their journey: To stay put or sell. Recently, there were two sets of reports highlighting the MTR dilemma. While the company has reportedly been in talks for an initial public offering (IPO), there was also unsubstantiated news of cigarette-to-food major ITC in talks to buy the heritage company. When asked, Bhasin and Sharma declined to comment.

The MTR story, the duo reckons, can be understood from one lens. “After buying the company, we never talked about Orkla. It was always MTR,” says Bhasin. “It will always be MTR,” adds Sharma.

Sunay Bhasin, CEO, MTR and Sanjay Sharma, CEO and director Orkla India. Image: Selvaprakash Lakshmanan for Forbes India

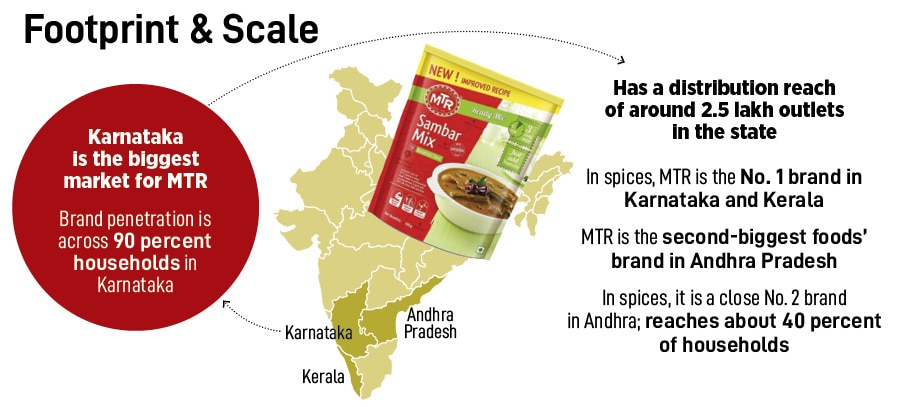

Sunay Bhasin, CEO, MTR and Sanjay Sharma, CEO and director Orkla India. Image: Selvaprakash Lakshmanan for Forbes India Statistics buttresses Bhasin’s claims. In Karnataka, which is the biggest market for MTR, the brand penetration is across 90 percent of the households. “We have a distribution reach of around 2.5 lakh outlets in Karnataka,” claims Bhasin.

Statistics buttresses Bhasin’s claims. In Karnataka, which is the biggest market for MTR, the brand penetration is across 90 percent of the households. “We have a distribution reach of around 2.5 lakh outlets in Karnataka,” claims Bhasin.