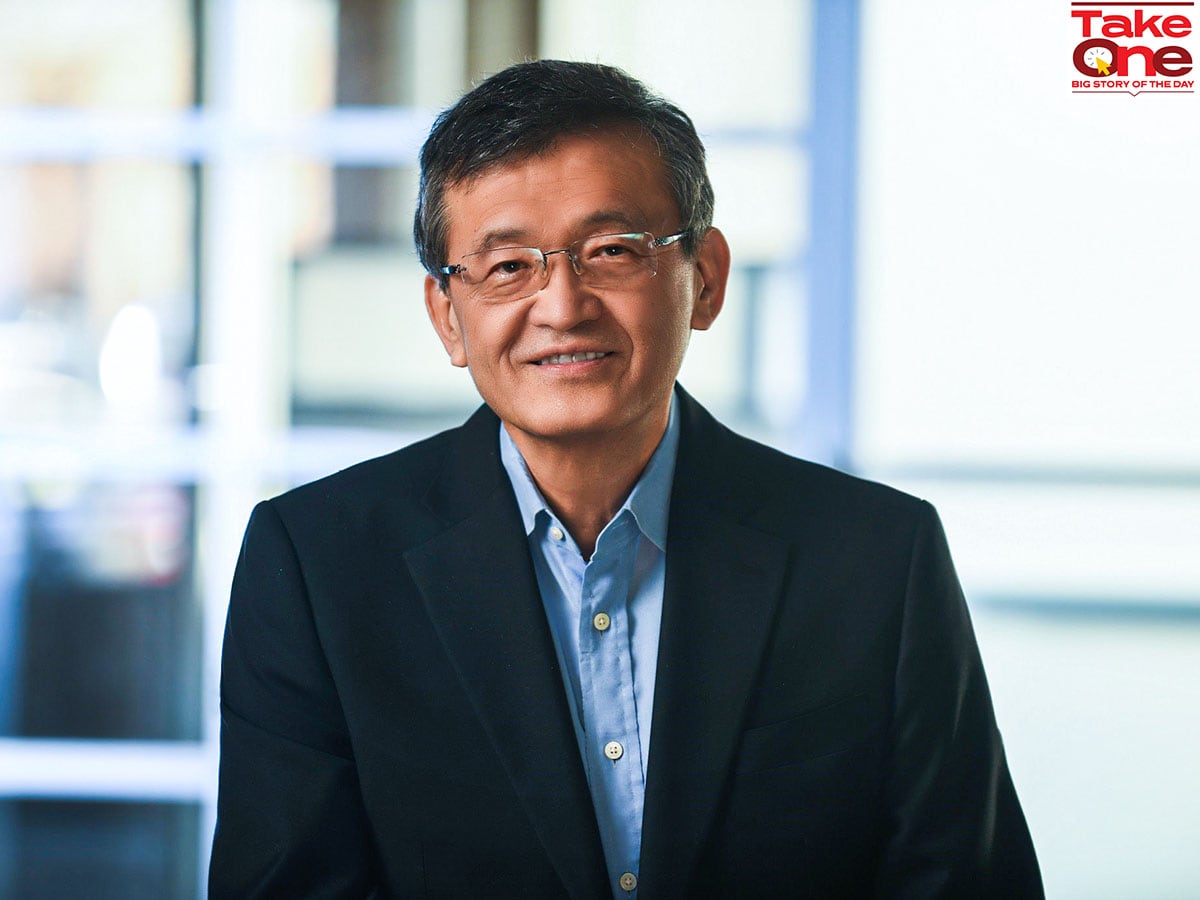

In July last year, Lip-Bu Tan flew down to Bengaluru to inaugurate a deeptech fund his friend had started, the day after he attended the wedding of billionaire Mukesh Ambani’s son Anant Ambani in Mumbai. The venture capital fund’s launch got some modest media coverage and Tan flew back the same day.

On March 12, Tan was named CEO of Intel Corp, an American tech icon that helped give Silicon Valley its name, but today a company that is facing the prospect of being left behind in the fast-changing world of artificial intelligence (AI).

Intel shares surged on the Nasdaq to end last week close to 19 percent higher on the news. Tan is founding chairman of the global VC firm Walden International and former CEO and chairman of Cadence Design Systems, one of the world’s biggest electronic design automation companies. He is also the founding managing partner of Celesta Capital, a deep-tech focused VC firm.

Tan, 65, has previously served on Intel’s board. He starts as CEO tomorrow, according to the global chipmaker’s March 12 press release announcing his appointment. He is replacing his predecessor Pat Gelsinger, who was ousted by the board in December after about four years at the helm. He will also re-join the board, which he had left in August 2024.

“Lip-Bu’s understanding of the semiconductor industry is unparalleled. He has seen it from every angle. His network and relationships in the industry are unparalleled,” Jaswinder Ahuja, corporate vice president, international HQ and India managing director at Cadence Design Systems, tells Forbes India in an interview.

Ahuja’s views here are his own, as a 40-year semiconductor industry veteran himself, and not to be attributed to Cadence in any way.

“There are very few people on the planet who can count the chairmen of TSMC, Samsung, Qualcomm or any other important semiconductor company in their close circle,” Ahuja says, of Tan’s depth and reach of relationships.

Engineering Focus

In a note sent on email to Intel staff that was posted on the company website, Tan says he is looking for an opportunity to “remake the company for the future,” adding that, in many ways, they should all see themselves as the founders of “The New Intel.”

“Under my leadership, Intel will be an engineering-focused company,” he writes. He promises to “empower leaders to take ownership and actions” that will contribute to restoring Intel as a world-class products company. He also put his back behind Intel’s aim to establish itself as a top-notch global foundry company as well.

“I subscribe to a simple philosophy: Stay humble. Work hard. Delight our customers,” he adds.

If he succeeds, it won’t be the first company he turned around. Tan is widely credited with taking charge of Cadence and effecting a spectacular rise. He served as CEO of Cadence from 2009 to 2021, “where he led a reinvention of the company and drove a cultural transformation centred on customer-centric innovation,” Frank Yeary, independent chair of Intel’s board, said in a statement on the company’s website on March 12.

On Tan’s watch as CEO, Cadence more than doubled its revenue, expanded operating margins and delivered a stock price appreciation of more than 3,200 percent, Yeary noted. Tan served as a member of the Cadence board of directors for 19 years, from his appointment in 2004 through his tenure as CEO and then as chairman from 2021 to 2023.

Ahuja recalls that when Tan started as CEO at Cadence, he took an outside-in approach, paying much attention to feedback from customers and partners, meeting more than 300 customers in the first six months at the helm.

“He’s a great listener. In the same day, he can meet the CEO of a company, the VP of engineering and the supervisor on the factory shop floor, and give each one the same level of attention and leave each one feeling he got something out of the meeting,” Ahuja says.

“He can have back-to-back meetings with a multi-billion-dollar public company and a struggling startup, and he’ll give them the same focused attention,” says Ganapathy Subramaniam, founding partner at Yali Capital, in Bengaluru, the deep tech VC firm whose first fund Tan inaugurated in July last.

He also has an uncanny strategic-thinking ability, these experts say, to see where the industry is moving. As a seasoned investor in the semiconductor sector, he sees a large number of companies at every investment stage, from young startups to established enterprises, and has the ability to put his finger on the technologies likely to hit the market five years down the line and the trends they might touch off.

Some of his decisions will likely be the classical build-versus-buy ones that top executives have to make all the time, Ahuja says.

For example, Tan decided Cadence needed to build out its semiconductor IP business, and made targeted acquisitions in the area. Semiconductor IP are building blocks of design for components or parts of components such as a USB connector or memory interfaces and so on.

Tan faces a daunting task at Intel, whose troubles have been years in the making, well before Gelsinger’s tenure. Intel’s fall from its iconic status was underscored by its removal from blue-chip Dow Jones Industrial Average index, in November last after a 25-year reign. Nvidia, whose GPUs dominate the AI chip landscape today, was added instead.

The change reflected the stunning rise of Nvidia on the back of demand for its chips for their ability as AI accelerators. It also marked an historic end of an era for Intel that is yet to offer a serious competing product.

Initial projections for Intel’s vaunted AI chip, called Gaudi, showed it was not getting the traction the company had hoped for. Gelsinger confirmed in October the company would not be meeting its first $500 million target in Gaudi sales in 2024.

A small source of relief was when Intel finally won a $7.86 billion grant under the US government’s CHIPS and Science Act, aimed at supporting local semiconductor manufacturing industry’s expansion.

The grant, slightly lower than the initially announced $8.5 billion, reflects Intel’s $3 billion contract with the US Department of Defence, also funded by the CHIPS Act, CNBC reported on November 25. US President Donald Trump, however, aims to repeal the act, which was signed into law by his predecessor Joe Biden in 2022.

The AI story is far from over, however, and most experts agree the industry has just scratched the surface, while Nvidia currently dominates one type of use case or a specific set of applications, in training large AI models on data centres.

What will emerge in the future by way of new applications of AI, the processor architectures that would be needed, edge AI, and indeed AI in the data centres, “we don’t know exactly the answers to all of that,” Ahuja says.

In other words, Tan may have something of a runway, but it will take all of his experience, networks and ability to tap the ecosystem – from Silicon Valley to Bengaluru – to deliver the products that will “delight” the customers and, as he points out in his email to staff, the shareholder value that should follow.

Also read: The global race for AI chips intensifies. Where does India stand?

India Connects

Tan, born in Malaysia, raised in Singapore and settled as a US citizen, has always had a global outlook. At his first VC firm Walden International, which he founded in 1987, he sought to make investments in multiple markets including India.

He was a founding investor in Bengaluru-based IT services company Mindtree, in August 1999. He was on its board, Krishnakumar Natarajan, co-founder and former CEO of Mindtree and partner at the Bengaluru VC firm Mela Ventures, tells Forbes India in an interview. Tan exited after Mindtree’s initial public offering (IPO) in 2007.

“We’ve kept in touch and on some of my visits to the US, I go meet him,” Krishnakumar says.

As it happens, in the last five-six months, Krishnakumar has had more interactions with Tan, as his own interests in deep tech have grown, through his VC firm Mela Ventures. And on a recent visit to the Bay Area, Tan also encouraged him to meet several startups that were doing innovative work in generative AI other technologies, the Indian IT entrepreneur recalled.

“His energy levels are still amazingly high, and he’s very much in touch with what is happening at the ground level,” Krishnakumar says.

It was through Somshankar Das, another entrepreneur in the US-India corridor who had been roped in by Tan as a general partner who set up Walden’s India office, that the firm invested in Mindtree. Das and the founders of Mindtree met via a common acquaintance.

“Even in 99, Lip-Bu was clear that India was a market he should look at,” Krishnakumar says. Investments such as Mindtree were part of Tan’s effort to back credible founders and through those partnerships understand the market, he says.

At Yali Capital, Subramaniam sees himself as a permanent student of Tan. Subramaniam himself is a semiconductor industry veteran, with his 35-year experience spanning Texas Instruments, two semiconductor startups that were both acquired – one by Cadence and the other by Micron Technology – and Celesta Capital, before starting Yali. He co-founded Yali with Mathew Cyriac, the former co-head of Blackstone India PE.

It was Ittiam Systems’s founder Srini Rajam, who’d previously recruited Subramaniam into Texas Instruments (Rajam led TI India before founding Ittiam), who later introduced him to Tan, around 2009, Subramaniam recalls. Tan was an investor in Ittiam as well, recognised for its innovations in the area of digital signal processing.

Subramaniam was building Cosmic Circuits, his first startup. “We were self-funded and never got to take any money from Lip-Bu,” he recalls. “But I got to meet him every time he travelled to India, and he was always generous in sharing his experience,” the Indian entrepreneur and investor recalls.

At one point in Cosmic Circuits, Subramaniam credits Tan with dissuading him from making a particular decision that saved his company. “The details are still sensitive, but all I can say is that his advice saved me from a very big mistake,” he says.

Cosmic Circuits was acquired by Cadence in 2013, and Subramaniam’s second startup, Cirel Systems went on to sell 70 million integrated circuit chips and it was acquired by Micron in 2023.

‘If anyone can …’

Tan’s ability to display remarkable courtesy and humility in his interactions, is something that leaves an impression on anyone who meets him, as attested to by people like Subramaniam. “To this day, if you visit him at his home, when you leave, he’ll walk to the gate and wait for your car to exit, and this happened to me in January,” he recalls.

Being on time is another simple discipline for Tan. Often, Subramaniam’s calls with him are early morning Pacific Time and more often than not, “he’ll be already there, with his breakfast cereal bar and a banana in hand, when I join the call,” the Indian entrepreneur says.

“And he doesn’t have jet lag, wherever he goes. He’s active from the moment his feet hit the ground.” Tan keeps fit by swimming every day, and he tries to keep it up even when he travels, Subramaniam says.

In college, Tan played basketball, and he noted in his email to Intel staff that an enduring lesson he learnt in university was as an athlete, to be able to trust his teammates and believe in them.

Subramaniam finally did get to take funding from Tan, not as an entrepreneur, but as a VC investor. Tan is a significant backer of Yali as a limited partner and advisor. The firm is soon looking to hit the final close of its first fund, which likely to be slightly larger than the Rs. 810 crore originally announced in July 2024.

Consistency is another characteristic of Tan that senior industry investors attribute to him. “He’s seen all the ups and downs and he’s been consistent through all phases,” Karthee Madasamy, founding managing partner at MFV Partners, a US-based deep tech VC firm in the San Francisco, tells Forbes India in an interview.

For example, there was a time between 2010 and 2016-17 “when nobody touched semiconductors for venture investments, pretty much everybody ran away from the sector, Lip-Bu was probably the only investor to consistently keep investing,” Madasamy says. Tan’s consistency has earned him great goodwill in the semiconductor ecosystem, he says. “Nobody else has that.”

Tan holds a bachelor’s degree in physics from Nanyang Technological University in Singapore, a Master’s degree in nuclear engineering from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and an MBA from the University of San Francisco. In 2016, he received the Global Semiconductor Alliance’s Morris Chang Exemplary Leadership Award, and in 2022, he received the Robert N. Noyce Award, the US Semiconductor Industry Association’s highest honour.

As Intel’s CEO, Tan is to receive $1 million as salary, up to 200 percent in performance bonus, and about $66 million in long-term stock options and new-hire incentives, according to a company filing with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), the US capital markets regulator.

Tan has also agreed to purchase and hold $25 million in Intel stock within the first 30 days of his taking the CEO’s position, as a gesture of his commitment to Intel, according to the filing.

The combination of returning Intel to product leadership with chips for AI and data centres and executing on its newer foundry plan in the face of competition from a giant like TSMC, and in a timeframe that investors might be willing to be patient with, might intimidate a lesser person.

Across the industry, and with every expert contacted by Forbes India for this story, there is consensus on one sentiment. As each one of them said: “If anyone can turn Intel around, it’s Lip-Bu.”