Following the first batch of 40 Tejas aircraft, HAL is supposed to make 83 Tejas Mk1As, while also designing and developing the Mk2 variant

Following the first batch of 40 Tejas aircraft, HAL is supposed to make 83 Tejas Mk1As, while also designing and developing the Mk2 variant

It was a sight not many had anticipated.

After all, the setting was the Indian government’s flagship defence exhibition, the Aero India 2025, being held at the Indian Air Force’s (IAF)premier transport base, Air Force Station Yelahanka, in Bengaluru. In attendance were the world’s biggest aerospace companies—from US-based Boeing and Lockheed Martin, to Dassault, Safran, and Thales from France, and the Russian government-owned Sukhoi. In all, the exhibition featured over 900 exhibitors, all trying to woo the Indian government into handing them lucrative defence contracts.

Usually, the top brass of the IAF flies down for the coveted event, since many of them have a say in making purchases for the fourth largest Air Force in the world. For the first time, the event also featured the Su-57, one of the world’s most advanced fifth-generation fighter aircraft, and the US-made F-35, another fifth-generation fighter aircraft at the same venue.

Yet, even as those aircraft were enthralling the audience, in another corner of the tarmac, the IAF’s chief, Air Chief Marshal AP Singh, sat in the cockpit of the indigenously developed Hindustan Jet Trainer (HJT) 36, built by Bengaluru-headquartered public sector company Hindustan Aeronautics Limited (HAL), only to appear despaired, before publicly reprimanding HAL officials who were standing beside the aircraft.

“I can only share our concerns and requirements,” Singh told them from the cockpit, as seen in a video that went viral on social media platform X. “At this point, I have no confidence in HAL, which is not a good situation. I was promised that when I came here in February, 11 Tejas-Mk1As would be ready. And not even one is ready.”

The IAF is set to purchase over 150 of the indigenously developed Tejas aircraft from the homegrown HAL, the maker of the aircraft. And, for a few years now, especially with the Indian government pushing the Make in India narrative, many of Singh’s predecessors have been vocal about the need to purchase homegrown aircraft. Singh’s recent comments though are seen as something of a wakeup call.

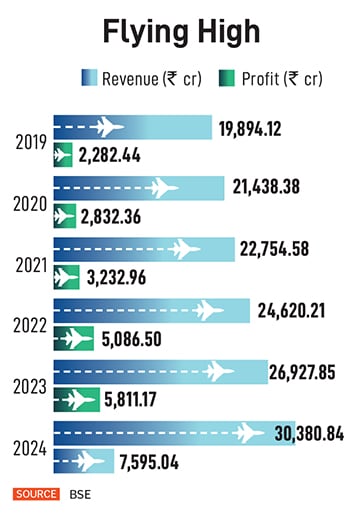

The concerns that Singh has raised are deeply worrying, especially coming at a time when the IAF’s squadron strength has fallen to just 31 from the sanctioned strength of 42. It also raises eyebrows about the capabilities of the country’s premier aerospace manufacturer, HAL, which had over the past two years also become a darling of the Indian investor, riding high on the Make in India initiative.

“The first Tejas aircraft flew in 2001,” Singh had said in January this year. “Then, the induction started another 15 years later, in 2016. Today, we are in 2024, I do not have the first 40 aircraft also. This is the production capability. We need to do something. I am very convinced that we need to get some private players in. We need to have competition. We need to have multiple sources available so that people are wary of losing their orders. Otherwise, things will not change.”

A spokesperson for HAL declined to comment and instead referred to public statements from HAL’s newly appointed managing director, Dr DK Sunil, who has publicly stated that the company is working with the IAF, and deliveries of the Tejas will start very soon.

Tejas, the bigger worry

At the centre of the growing concerns about HAL’s capabilities is the inability to deliver the promised Tejas aircraft to the IAF.

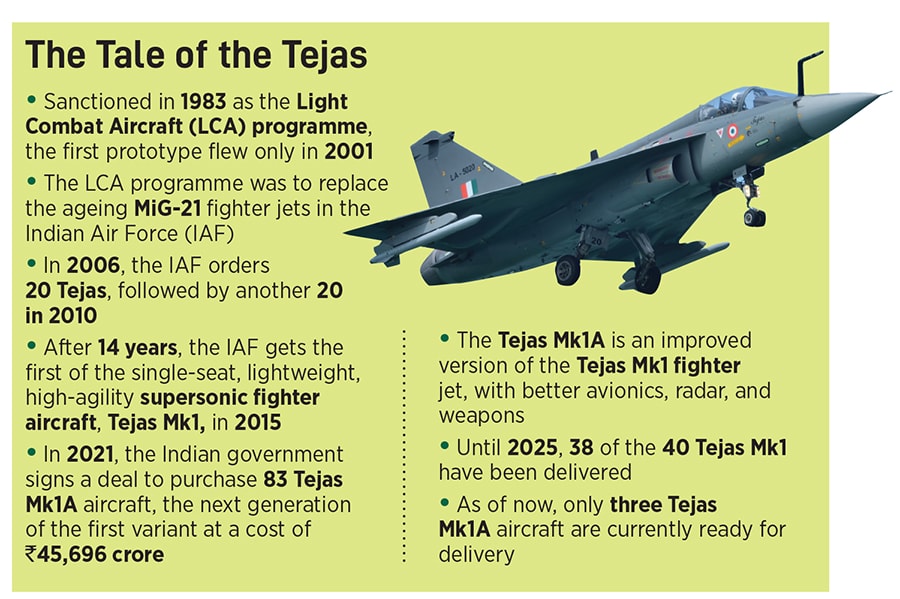

Tejas, the fighter aircraft, was initially conceived in the early 1980s but faced multiple headwinds before its induction into the IAF in 2019. That’s a nearly four-decade-long wait. A typical production cycle involves the design and development phase before prototypes are built and tested. That’s followed by a limited series production and a full series production.

So far, the company has delivered 38 of the 40 Tejas aircraft that were supposed to be delivered to the IAF. Post that, the company is set to manufacture 83 Tejas Mk1A aircraft, while also starting the design and development phase for the Tejas Mk2 aircraft. The Mk1A is designed as an interim aircraft between the Mk1 and Mk2, with features such as air-to-air refueling, advanced avionics, and electronic warfare suites. HAL plans to complete the delivery of the Mk1A by 2028 with an ambitious target of inducting the Mk2 by the same year.

Of the 83 Tejas Mk1A, estimated to cost some ₹45,696 crore, 73 are fighter aircraft, with 10 being trainer aircraft. The Tejas Mk2 contract meanwhile is estimated to be worth ₹67,000 crore. While the Tejas Mk1 was designed to replace the aging MiG-21 fleet, the Tejas Mk2 is expected to replace aircraft such as the Mirage-2000, MiG-29, and Jaguars.

To do all that, the government-owned company had set plans to ramp up its production from eight aircraft a year to 16 in 2023, which could go up in the final year of delivery. But that doesn’t seem to have materialised. The IAF wants to build six squadrons of the Tejas Mk2, and the prototype is expected to be tested in 2026.

“HAL cannot be held solely responsible for the manufacturing problems encountered by the Tejas production line,” says Abhijit Apsingikar, senior analyst for defence at London-based consultancy firm GlobalData.

“While HAL has experienced significant challenges in managing vendor supply chains, which have caused production disruptions, Tejas’s production has also stalled as a result of US-based General Electric’s supply chain problems with the F404-GE-IN20 afterburning turbofan engines. The efficiency of HAL’s manufacturing lines has been severely undermined as a result of the company having to deal with both systemic problems and outside supplier concerns that are out of its direct control.”

“While HAL has experienced significant challenges in managing vendor supply chains, which have caused production disruptions, Tejas’s production has also stalled as a result of US-based General Electric’s supply chain problems with the F404-GE-IN20 afterburning turbofan engines. The efficiency of HAL’s manufacturing lines has been severely undermined as a result of the company having to deal with both systemic problems and outside supplier concerns that are out of its direct control.”

General Electric, the American multinational, is tasked with supplying the F-404 engines for the Tejas Mk1. HAL had signed a $716-million deal with GE in August 2021 for 99 F-404 aircraft engines and support services for the LCA-Mk1A. But, so far, HAL has only been able to manufacture three Tejas Mk1A aircraft, with two more in the final stages of production, using available engines.

In addition, HAL and GE are currently negotiating a co-production agreement for the more powerful GE-F414 engines, signed during Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s visit to the US in 2023, to be used in the Tejas Mk2. HAL has three production lines in place: Two in Bengaluru and a third in Nashik. “HAL’s negotiations for the F-414 engines have encountered challenges, with GE Aerospace demanding an additional $500 million over the previously agreed contract value of $1 billion,” brokerage firm Prabhudas Lilladher said in a report on February 13. “Despite this, HAL remains optimistic about finalising the F-414 deal by the end of FY25.”

“While supply chain management and production scheduling are significant challenges for HAL, the state-owned OEM also struggles with poor vendor selection and bureaucratic red tape,” adds Apsingikar. “To address these issues, the Ministry of Defence [MoD] must incentivise HAL to be more open to private sector collaborations and encourage greater private sector involvement in Tejas production. Additionally, the government needs to step in to help resolve supply chain issues, particularly those involving foreign partners like GE.”

Also read: India’s defence companies have been on a roll. Will it change under Modi 3.0?

The curious case of HAL

HAL traces its roots to the Mumbai-based businessman, Walchand Hirachand Doshi, who also founded India’s first shipyard and car factory.

Initially set up as Hindustan Aircraft Limited in Bengaluru in 1940, Hirachand partnered with the Mysore government, then under the King of Mysore, to set up the aircraft manufacturing facility. In March 1941, understanding the strategic importance of the business, the government of British India became a shareholder, and finally by 1942 took over the management as World War 2 was being fought.

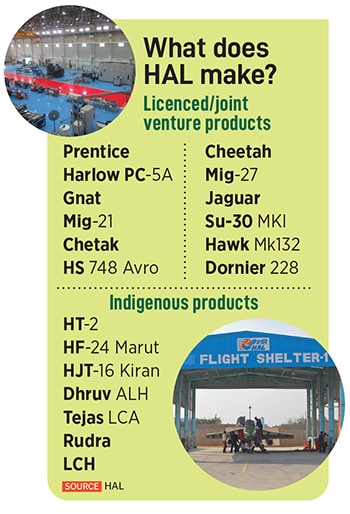

In 1941, the company collaborated with the Inter-Continental Aircraft Company of the USA, to manufacture the Harlow Trainer, followed by the manufacturing of Curtiss Hawk Fighter and Vultee Bomber Aircraft. By 1951, shortly after India’s independence, the company was put under the control of the country’s defence ministry.

Over the next few years, the company went on to build engines under licence, while also designing and developing India’s first indigenous aircraft in HT-2 Trainer. Over 150 Trainers were manufactured and supplied to the IAF and other customers. That was followed by the successful design and development of its aircraft including the two-seater Pushpak, meant for flying clubs, the HF-24 Jet Fighter (Marut), and the HJT-16 Basic Jet Trainer ‘Kiran’.

Over the next few years, the company went on to build engines under licence, while also designing and developing India’s first indigenous aircraft in HT-2 Trainer. Over 150 Trainers were manufactured and supplied to the IAF and other customers. That was followed by the successful design and development of its aircraft including the two-seater Pushpak, meant for flying clubs, the HF-24 Jet Fighter (Marut), and the HJT-16 Basic Jet Trainer ‘Kiran’.

By 1963, the Indian government, as part of its plan to increase licensed manufacturing in India, set up Aeronautics India Limited (AIL) to manufacture MiG-21 aircraft. AIL also took over the Aircraft Manufacturing Depot of the IAF to manufacture airframes for the HS-748 transport aircraft before the government decided to merge HAL with AIL in 1964.

HAL, the new company, was tasked with the design, development, manufacture, repair, and overhaul of aircraft, helicopters, engines, and related systems like avionics, instruments, and accessories.

“HAL’s challenges are not rooted in technological inefficiency, but rather in supply chain and vendor management issues, as well as quality control,” adds Apsingikar.

“Persistent problems with production scheduling and, more specifically, vendor quality, have been largely linked to the vendor selection process. A major disruption occurred when the Indian Ministry of Defence decided to outsource the production of critical body and fuselage components. HAL had to rapidly adapt to a new model, acting as a lead integrator while subcontractors handled the manufacturing of specific components. This shift from controlling the entire production process led to significant integration challenges, as the company struggled to coordinate a geographically dispersed vendor network.”

What lies ahead?

For now, the Indian government has stepped in, and a committee it set up has advocated greater collaboration between the private sector, the Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO), and Defence Public Sector Units (DPSU) to help with meeting the IAF’s requirements.

“The report also underscores the need for impetus to enhance ‘Aatmanirbharta’ in the aerospace domain with the private sector complementing the efforts of DPSUs and DRDO,” a statement from the Ministry of Defence said on March 4 about the report submitted by the committee. This means, private sector companies could see a greater role in aircraft manufacturing if delays persist.

Meanwhile, it’s not just the Tejas that have raised concerns for HAL. A line of 300 helicopters, named Dhruv advanced light helicopters (ALH), has been grounded since January 5, after a fatal crash involving one of the models in Gujarat.

Before the mishap, the Dhruv helicopters had experienced similar accidents, that have claimed officers and soldiers of the defence forces. Not just that, in 2015, Ecuador terminated a contract with HAL after four of the seven ALH platforms it purchased from the company were involved in crashes.

“Serious issues with the service life and quality of certain critical components in the Dhruv helicopters have contributed to several accidents,” adds Apsingikar. “However, halting production is not the solution. As complex flying machines, rotorcraft naturally experience higher levels of wear and tear. The inherent complexity of their mechanics and flight dynamics also makes helicopters a relatively risky platform. Given these factors, catastrophic failures in ALHes are not uncommon, especially when considering the challenging environments in which they are typically deployed.”

Despite these challenges, Dhruv remains essential to the Indian Army, Air Force, Navy, and Coast Guard. “As such, the production line cannot be shut down, since HAL is responsible for their ongoing maintenance, repairs, and the provision of spare parts and components throughout their service life,” adds Apsingikar.

So where does HAL go from here now? For now, with the government’s blessings its quite unlikely that the company will face any headwinds. “HAL is the primary supplier of India’s military aircraft, has long-term sustainable demand opportunity owing to government’s push on indigenous procurement of defense aircraft, and a robust order book with a 3-year pipeline of ₹2 trillion,” says Prabhudas Lilladher.

“Even with local production of foreign-designed aircraft and helicopters, relying on imports to meet the Indian military’s vast rotorcraft needs would be unwise,” says Apsingikar. “Such an approach would only increase dependence on foreign governments for the operation and sustainment of these platforms.”

But, growing concerns among the echelons of Vayu Bhawan, the headquarters of the IAF, could pose significant troubles if the company isn’t ready to meet timelines. The last time the Indian government made a significant foreign purchase was in the case of 36 Rafale aircraft, and with US President Donald Trump pushing for greater defence contracts between the two nations, HAL might need to prove its mettle sooner than anticipated. And that means getting things in order as quickly as possible.