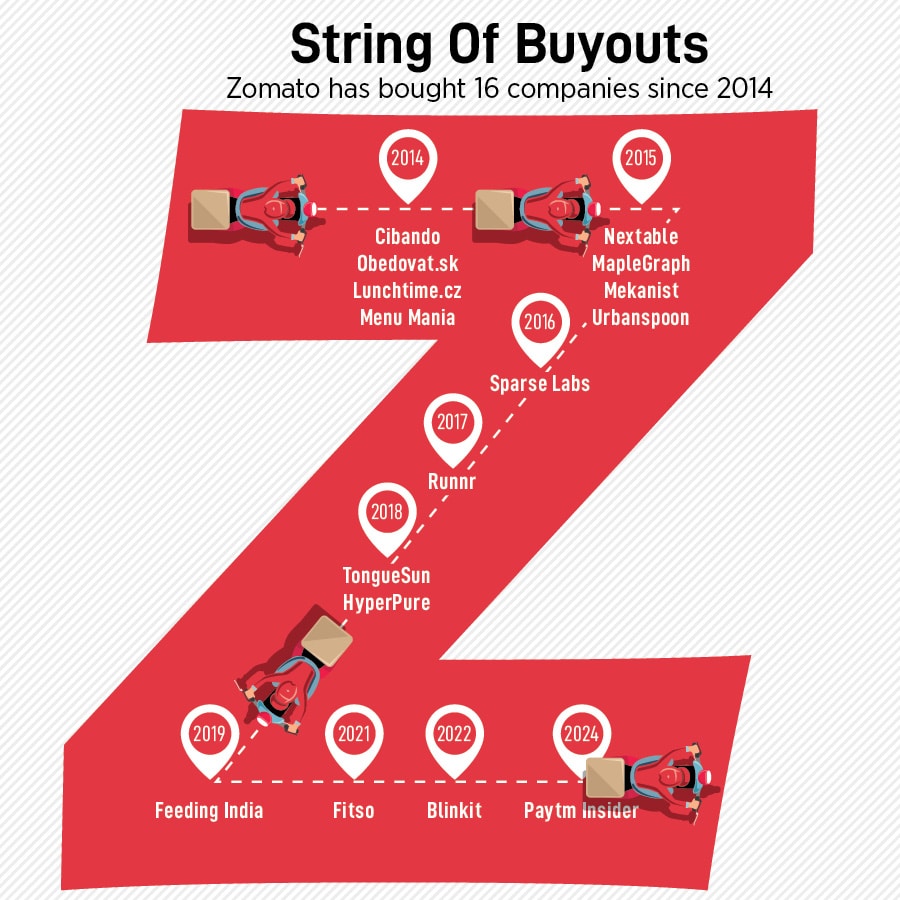

Christmas was around the corner. But for Deepinder Goyal, December of 2021 was turning out to be a month less of cheer and more of unease. The co-founder and CEO of Zomato invited Akshant Goyal, the CFO, to his house in Gurugram to discuss what was weighing on his mind: Whether Zomato should gobble up the whole of Blinkit.

Five months earlier, in July that year, Zomato had bought 9.3 percent equity in Grofers, an online grocery delivery company. In August, it wrote the opening chapter of the quick commerce (QComm) saga in the country with non-food deliveries in—scarcely believable at that time—10 minutes. In December, Grofers rebranded itself as Blinkit to reflect its transition from next-day delivery to QComm.

Goyal was no longer satisfied with the 9.3 percent bite. He wanted all of it.

Truth be told, he was not just toying with the idea, he was desperate to do it. His own attempts at online grocery delivery had not delivered the goods.

He first tried his hand at it with Zomato Market in April 2020—at the height of the Covid-induced lockdown, when online orders and deliveries boomed. It rolled out across 80 cities, but within two months started to scale down, hobbled by logistical challenges. Once the lockdown began to ease, Zomato Market was shuttered.

It showed Goyal the cash-guzzling nature of the business and poor customer retention. Food delivery now became the sole focus for Zomato, but not for long.

Soon Goyal would make his second attempt at grocery. In July 2021, the same month Zomato bought into Grofers, it started a pilot for 45-minute grocery delivery in Delhi-NCR. The experiment lasted all of three months. But this time there was a clear path ahead, because of the Grofers investment. It was enthused by Grofers’s progress with 10-minute delivery, and Goyal spotted a positive change in user behaviour.

“We stopped stocking things in the fridge,” he says in an interview with Forbes India. “We were ordering real time.”

After a Grofers store opened next to Zomato’s headquarters in Gurugram in July 2021, Goyal would order on the app several times a day. By December, he was sure he wanted the whole thing.

“We knew it was probably going to be super hard to make money… but the same question was with food delivery when we started,” says Goyal. “We could not afford to miss the quick commerce opportunity.”

On June 27, 2022, Zomato bought Blinkit, triggering negative reactions from the stock market. A loss-making company had bought another loss-making company, and Zomato was seen to be deviating from its core of food delivery.

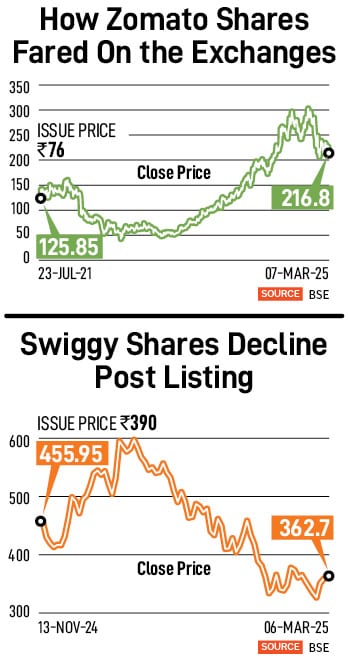

Among quick commerce companies, Zomato was the first to go public, debuting on the stock exchanges in July 2021. Its share price nearly halved in just a year, falling to its lowest level at ₹41.65 on July 26, 2022, a month after the announcement of the Blinkit acquisition.

Since then, QComm has emerged as India’s fastest-growing ecommerce segment, with Blinkit, along with Swiggy Instamart and Zepto, basking in the glow.

QComm’s size has jumped from $0.3 billion in FY22 to $3.8 billion in FY24, according to the latest research by Blume Ventures, and is likely to touch $7.1 billion by the end of the current financial year (FY25). Monthly transacting users are likely to touch 26.3 million, from 14.4 million last year. The low labour cost in India, along with high-density cities, make QComm’s unit economics work, adds the report.

To no one’s surprise, others are moving in. Amazon is running QComm pilots in Bengaluru. Flipkart has ramped up its QComm vertical, Minutes, and reportedly plans to open 500 dark stores this year. Cloud kitchen player Rebel Foods recently rolled out QuickiES, a 15-minute delivery service.

In the midst of this, there is another rebranding, this time for Zomato: In February, it became Eternal. Goyal explains that Eternal is not about living forever. “What it means is if you do not take the right actions and decisions today, you might die,” he says.

However, despite the rising tide of quick commerce and a new name, Eternal faces ancient questions.

Quarterly Blues

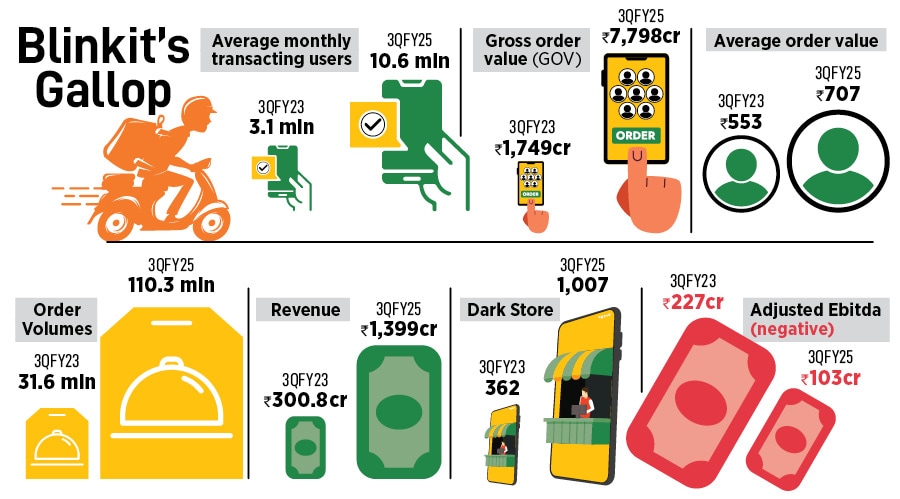

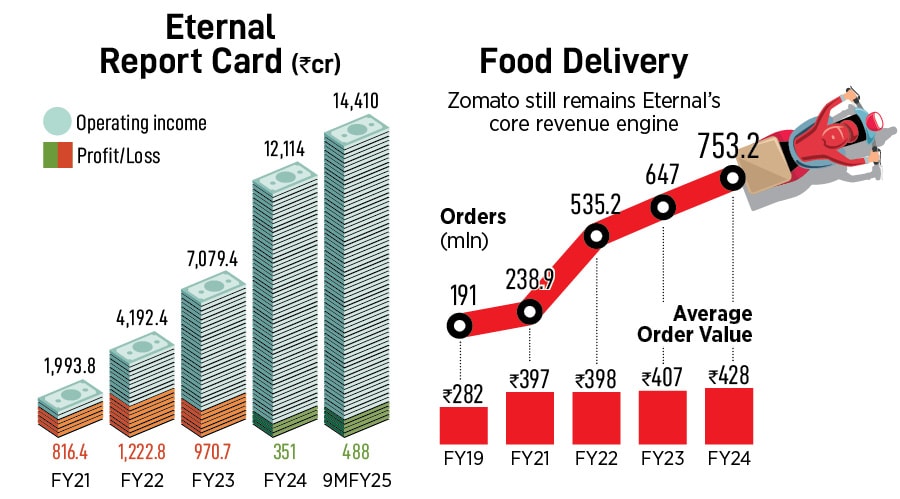

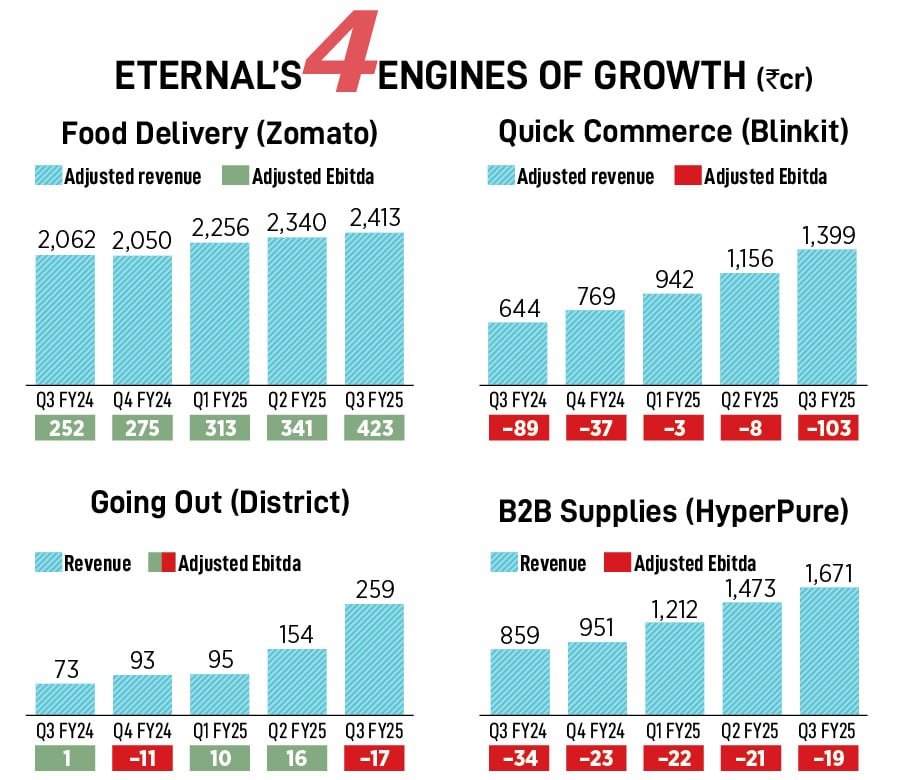

It reported poor results for the third quarter of the current financial year, showing rising losses in QComm, muted growth in food delivery, and high capital expenditure (capex) incurred on dark stores for 10-minute deliveries. Despite the celebratory mood around QComm, the financial numbers for Blinkit are no reason to pop the champagne. It showed soaring losses, although the Ebitda improved, on the back of a brisk expansion of dark stores.

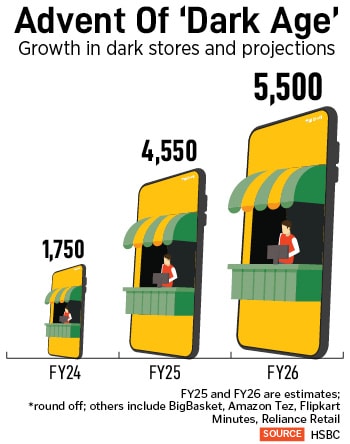

Dark stores are driving every QComm company. “They are the heart of quick commerce,” pointed out Chryseum, a financial services firm, in a report last year. They reduce delivery time and cost, thereby improving unit economics.

Also read: Swiggy is betting on quick commerce to become no. 1. Will it succeed?

Blinkit is set to reach its target of 2,000 dark stores by December—a year ahead of the plan. More than half of the new stores are in the top eight cities, from where Blinkit gets 80 percent of its business.

“We are seeing fairly healthy tractions in the smaller cities,” CFO Akshant Goyal said in an earnings call in January. He asserted that there would be no let-up in the hinterland push: “Looking forward over the next one year, a larger portion of our new stores will be in these smaller cities compared to what we saw last year.”

Speed and expansion have entailed high capex. That, the company said in a letter to shareholders, was the reason behind the quarterly increase in depreciation, adding that capex was likely to remain high for the next few quarters. That would mean more quarters of losses. “We do expect losses to continue,” the CFO outlined in the letter.

It does not help that the shadow of Zepto, flush with investor money ($1.3 billion in the bank at last count) and unlisted (meaning it has fewer shareholders to answer to), looms on the QComm landscape. Founded by Aadit Palicha and Kaivalya Vohra, it has furiously increased its dark store count from 200 in FY23 to an estimated 1,050 by the end of FY25, according to the report by Blume Ventures.

Its aggression is matched by a soaring report card: Revenue from operations surged 2.2 times in FY24, according to data from Entrackr, a media venture tracking startups and internet economy in India. Zepto makes high losses, but continues to burn cash in its sprint to race ahead of Blinkit.

Eternal’s Blinkit, on the other hand, needs to keep a firm eye on the bottom line, because markets are rarely kind to loss-making companies. Meanwhile, Swiggy’s Instamart —the third wheel of the QComm rollercoaster—is not far behind. From 421 dark stores, it is likely to end the current financial year with 1,004, predicts the Blume report.

Eternal’s Blinkit, on the other hand, needs to keep a firm eye on the bottom line, because markets are rarely kind to loss-making companies. Meanwhile, Swiggy’s Instamart —the third wheel of the QComm rollercoaster—is not far behind. From 421 dark stores, it is likely to end the current financial year with 1,004, predicts the Blume report.

Instamart is firing on all cylinders. “We have expanded the Instamart service to 84 cities,” Sriharsha Majety, cofounder and Group CEO of Swiggy, pointed out in a letter to shareholders in January. “Our investments are focussed on geographical expansion, customer acquisition, retention, and competitive dynamics.”

Food For Thought Meanwhile, for Eternal, trouble is brewing on another front. Its core business of food delivery is facing macro headwinds. “Currently, we are going through a broad-based slowdown in demand, which started during the second half of November last year,” said Rakesh Ranjan, CEO (food delivery vertical) of Eternal, in the shareholders’ letter this January.

The impact is evident in the slow growth in gross order value and adjusted Ebitda. What’s more worrying is the number of average monthly transacting customers in the first three quarters of this financial year: It has remained hemmed in between 20 million and 21 million.

Eternal’s third pillar, HyperPure, a platform that provides kitchen supplies and services to hotels, restaurants and caterers, has been logging decent revenue numbers but is yet to post a profit.

The latest and fourth pillar—District—started on an impressive note. Its new app, which houses going-out businesses such as dining, live events and ticketing, was rolled out last November and has so far had more than 6.5 million downloads. But it grapples with the same problems as Blinkit and HyperPure: Losses.

Another set of dampening news is the capex needed for Bistro, Zomato’s 10-minute food delivery app for snacks, beverages and meals. As with QComm, this is not Zomato’s first shot at quick food delivery. In March 2022 came Zomato Instant, ran in Delhi-NCR and Bengaluru, and folded after a year.

“We could not find the right economic model and hence shut it down,” Goyal said in the letter to shareholders in January. Another venture launched with much fanfare was the intercity food delivery service, Legends. It could not find the right product-market fit and shut down after two years in August 2024.

“We could not find the right economic model and hence shut it down,” Goyal said in the letter to shareholders in January. Another venture launched with much fanfare was the intercity food delivery service, Legends. It could not find the right product-market fit and shut down after two years in August 2024.

Last December, though, Zomato returned to 10-minute food delivery with Bistro. The going won’t be easy; it is expensive to set up kitchens for 10-minute food delivery. “It takes around ₹2 crore to set up a kitchen,” reckons Albinder Dhindsa, founder and CEO of Blinkit. The reluctance of food outlets to set up 10-minute delivery kitchens is another problem.

Zomato anyway has not been on restaurant owners’ Diwali gift list. For years, the National Restaurant Association of India has been at loggerheads with food aggregators, including Eternal, hurling accusations of unfair practices in discounting, handling of customer data, and in charging commissions from restaurants.

So, what is Goyal’s game plan. Surely, it has to have much more than a new name.