Anora swept the 2025 Oscars, winning five awards, including Best Picture and Best Director.

Anora swept the 2025 Oscars, winning five awards, including Best Picture and Best Director.

Filmmaker Pan Nalin and producer Dheer Momaya anticipated exciting times as they left for the United States after their Gujarati film Chhello Show (The Last Film) was chosen as India’s official entry for the 2023 Oscars. When they landed on November 5, four months before the awards ceremony, their publicists dashed their hopes in the first meeting itself, saying, “You guys stand no chance, don’t spend money on the campaign.”

Though they were “economically devastated” having made the film for Rs9 crore and spending another Rs4 crore on marketing it in India and abroad during its release, Nalin, who had sold his house in Borivali, Mumbai, to fund his directorial venture, saw this as a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity and decided to give it their best shot with the money they had. Confident that the movie will get a lot of love, he decided to stick around and return to India only when the limited amount ran out. He did exactly that.

To his surprise, the film was among the 15 shortlisted for the Oscar’s International Feature Film category soon after, and he, along with Momaya, had to take the flight back to the US. This time, they spent Rs5 crore on an intense campaign—from organising multiple screenings to publishing advertisements in newspapers—to create buzz about the film. Chhello Show eventually did not make it to the last five.

More Than Just a Good Film

It takes a lot to win an Oscar. Filmmakers and marketing professionals concede that it goes beyond just making a good film—it also needs lots of money. Discussions on the subject gathered steam after Anora swept the 2025 Oscars, winning five awards, including Best Picture and Best Director. Produced and distributed by Neon, the independent American film about a sex worker from Brooklyn marrying the son of a Russian oligarch spent $18 million—three times its budget of $6 million, the lowest on the Best Picture shortlist—on marketing, promotions and its Oscar campaign.

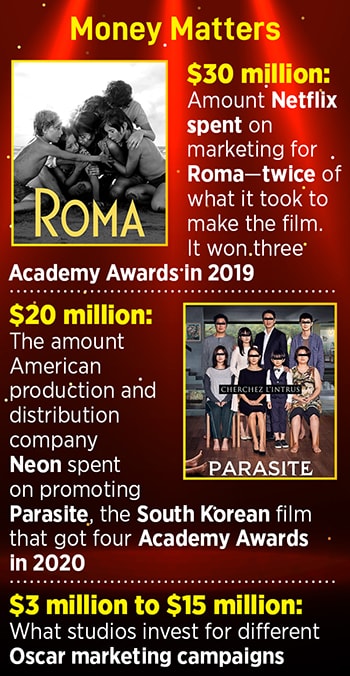

Neon had shelled out $20 million for Parasite, the Korean film made at a cost of $11.4 million that went on to win four Academy Awards, including Best Picture and Best Director, in 2020. Besides holding screenings, Neon had hired Oscar consultants and a PR agency, wooed opinion leaders in the American film industry, launched an awards campaign and leveraged online platforms.

For Anora, the campaign also involved putting up a pop-up merchandise sale in a tow truck in a parking lot in Los Angeles to sell branded T-shirts and thongs. And instead of hosting the Academy members who would vote for the Oscars, the first screening was reserved for sex workers. The revelations about the film’s marketing budget had people across the globe on the internet debating if the Oscar can be bought.

“Everything starts with a somewhat good film because marketing alone cannot do magic. It then pretty much sums up to how much money you are willing to spend. Otherwise, even if you have an excellent film, you will not go far,” Nalin tells Forbes India, adding that Chhello Show should have had a minimum $1.7 million (Rs16 crore) for the Oscar campaign alone.

Ritika Bhatia, executive producer of independent studio Drishyam Films, agrees. She realised the enormity of an Oscar campaign when she went to promote their film Newton at the Academy Awards in 2017. “The quality or ‘merit’ of the film is literally just one of a host of factors. Oscars are a lot about optics and pushing a narrative—why this film deserves an Oscar, why it needs to be seen, how is it changing the world or society, and so on. And that is done with marketing and advertising,” she explains.

The Amit Masurkar-directed Newton was made at a modest budget of Rs4.5 crore and the team spent over a crore on the promotions and publicity of the film in the run-up to the Academy Awards. They recruited an American PR agency which helped them host six to seven screenings over a six-week campaign, and advertised in trade magazines to further the chances of India’s official entry winning the trophy that year.

All that came at an enormous price. “The full-page ads in prestige trade magazines cost thousands of dollars… and their rates go up during the awards season. On top of that, the voting members have so many films to watch. We would count our screenings a success if we got just two or three members to attend,” admits Bhatia, who was then head of international alliances at Drishyam.

The Rs1 crore or so, she confesses, paled in comparison to what the Aamir Khan-starrer Lagaan—nominated as the Best Foreign Language Film at the Academy Awards in 2002—spent on its campaign even way back then. “Aamir had the resources to do that. But for indie films like ours, it’s extremely difficult. Someone has to back you and pour in millions,” says Bhatia.

Also read: From Demi Moore to Renee Zellweger, how midlife female actors are reclaiming Hollywood’s spotlight

Creating a Buzz

Shaunak Sen believes marketing is not the right word and that campaign is a more appropriate term. His documentary film All That Breathes made it to the final five nominations in 2023. According to him, filmmakers often club their theatrical and OTT releases with the Oscar campaign that begins around September. These months are also peppered with a litany of awards such as the BAFTA.

“The point is to stay visible or be in the conversation-points of people because you are jostling with tonnes of other films for attention and recall. And when you are competing with say, a pool of 10,000 films for your branch, it becomes a bigger competitive field. Consequently, you have to do a lot of screenings,” says Sen. “Therefore, many films hold events—with screenings, wine-and-dine afterwards and so on. And that requires money… to be on this hamster wheel of planes, hotels, shows. Sadly, not many of the under-funded films are able to cross the finishing line there because just to hold one event at one good theatre is not easy.”

Shwaas, the first Marathi film to be nominated for the Oscars, saw an overwhelming response to its shows in Los Angeles and New York. “Ninety percent of the audience were Americans,” says director Sandeep Sawant, jogging his memory back to his three-month experience at the 2004 Academy Awards. “The film had released in New York for a week, and there were five shows a day on Friday, Saturday and Sunday. Overall, we did 24 shows with at least one in each state. Of these, only two or three were free… for the others, we charged $1,000 (Rs45,000 then) a show.”

The film was made with Rs65 lakh—an impressive sum given that the budgets for Marathi films would be around Rs25 lakh or less that time. And though the Oscar campaign required massive funds, Sawant and his team left no stone unturned in raising them and giving Shwaas a fighting chance of creating history. “We gave full-page ads in four leading magazines. In some places, we had to settle for half-page ads due to budget constraints. We had hired a New York-based agency that was helping us navigate the tricky terrain,” says Sawant.

It takes a lot to win an Oscar. Filmmakers and marketing professionals concede that it goes beyond just making a good film—it also needs lots of money.

It takes a lot to win an Oscar. Filmmakers and marketing professionals concede that it goes beyond just making a good film—it also needs lots of money.

Money Talks

Financial heft plays a huge role in building a positive perception and chatter around films. “We have corruption, but Los Angeles has legalised corruption,” opines Nalin. He says one gets official emails mentioning the rates for an article in a newspaper. “We did one for $40,000. Some leading newspapers will not publish the review of your film if you are not their vendor—that is if the production company or the studio has never advertised with them. It’s a racket, but a legalised one… it’s invoiced,” adds Nalin, who is now a member of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences (Oscars) in the director’s branch and casts his vote for the prestigious awards.

He claims one has to pay $25,000 (Rs21 lakh) to be on some famous roundtables with directors. In the year that Chhello Show was in the shortlisted 15, he and six other filmmakers from that list were conspicuous by their absence at the roundtables because they could not pay. “It’s not a hidden truth,” emphasises Nalin. A group of Academy members, he alleges, charges $100,000 (Rs86 lakh) to go from screening to screening, and then promote your film among the voting fraternity.

“The awards ecosystem certainly works on some amount of lobbying,” rues Bhatia. “After my experience, I realised that while most awards, especially the Oscars, play their part in spotlighting and elevating certain deserving films, they cannot and should not be considered the only marker of a film’s quality and success.” In hindsight, she feels it would have helped had Newton roped in an international distributor and sales agent. “And getting a US release also helps to put your film on the radar of voting members. But all that requires even more money,” she points out.

Bringing in the Experts

India, filmmakers complain, is late to get off the mark when it comes to announcing its entry to the Oscars. As a result, while foreign films start their campaign months earlier, the Indian counterparts are at a disadvantage because of the delay. For instance, it hampers the prospects of getting a good publicist. “The best ones get snapped up before. We are left with those who don’t have a lot of experience in pushing foreign films,” explains Bhatia.

Publicists hold immense clout, and design and influence the Oscar campaign in unimaginable ways. “I thought we were hiring a publicist, but when we reached Los Angeles, we realised she is God,” guffaws Nalin, adding that they study the profiles of the Academy members and develop strategies accordingly. “Publicists have played a huge role in the past four to five years. My American Academy colleagues tell me that they never saw such power given to publicists before the pandemic. They do a surgical strike.”

Publicists hold immense clout, and design and influence the Oscar campaign in unimaginable ways. “I thought we were hiring a publicist, but when we reached Los Angeles, we realised she is God,” guffaws Nalin, adding that they study the profiles of the Academy members and develop strategies accordingly. “Publicists have played a huge role in the past four to five years. My American Academy colleagues tell me that they never saw such power given to publicists before the pandemic. They do a surgical strike.”

Like Bhatia, he too laments the fact that the good ones get lapped up by June-July. Apart from that, one has to lock horns with the big studios whose financial might makes them the favourites in the Oscar race.

In one of his first meetings, an agency was going to brief Nalin about the potential competitors in his category. The white board in the room—instead of having names of the producers, directors or films likely to be nominated—mentioned the streaming platforms and studios. “Right now, the biggest disruptors in the Oscar system are the streamers. They have so much money. And they need to get as many nominations as possible… if you look at the stock exchange on the day of the Oscars, you will see how much they gain,” he says, adding that they have an entire floor dedicated to awards and that they work on these campaigns all year through. In fact, now that he is among those who cast their vote across categories, he says he gets invites from a lot of studios for breakfast and lunch meetings.

Another change from the time of Lagaan and Shwaas is the emergence and popularity of social media. However, its impact on both the success of a film and the Oscar nominations is not clear. “Yes, the world has changed drastically since the time we were there. But I am not convinced if social media can make a difference. Can it pull people into the theatres? I am not sure,” says Sawant.

How Much is Too Much?

Anora’s strategy and marketing spend have got tongues wagging. But not everyone seems to think that the amount it spent is over the top. “Anora spending three times its budget appears dramatic because it is a low-budget film… $18 million does not sound extraordinarily big to me. In fact, there have been other films in the past that have spent more,” says Sen.

Netflix set a new standard with a whopping $30 million for its Oscar campaign on Roma—double the film’s production cost, according to a January 2024 Forbes article. It added that studios make investments in Oscar marketing campaigns that typically range from $3 million to an astounding $15 million per film.

Recalling the time Shwaas was in contention, Sawant says it’s hard to ascertain whether a competing film’s activities have an impact on the final outcome at the awards. However, Bhatia likens the Oscar campaign to any election, “where you are getting people to vote for you… and for that, you need to spend”. Nalin adds that at the end of the day, it all starts with a good movie. It’s evident, though, that after that there’s still a huge price to pay.