Bajaj’s EV manufacturing plant in Akurdi, Pune. So far in 2025, Bajaj has sold 54,348 electric two-wheelers

Image: Courtesy Bajaj Auto

Rakesh Sharma likens building India’s two-wheeler electric vehicle (EV) market to hosting a Diwali party.

“Sometimes you want to be the first one to throw a Diwali party and you want to do it by day after tomorrow,” says Sharma, the executive director at Bajaj Auto, who has been with the third largest two-wheeler maker in the country for almost 18 years. “So, you will assemble a buffet, which will be expensive, because you must buy everything from outside.”

The reference is to the host of brands that flocked to the Indian electric two-wheeler market in the last decade or so. “But you say it’s okay. I will take my time and do a post-Diwali party,” says the 62-year-old. “Then you cook at home, customise it, and go from the ground up. That will work out much cheaper and efficient.”

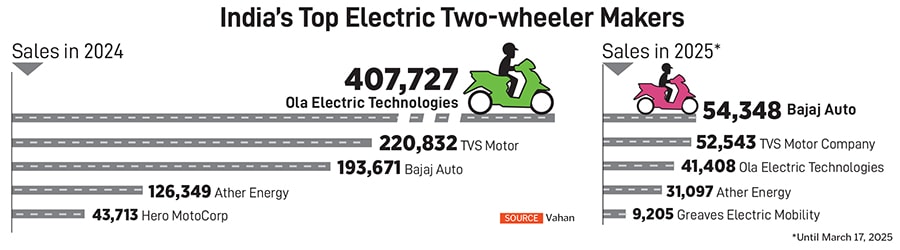

Bajaj Auto seems to have done the latter, with success. In December last year and February this year, Bajaj, the maker of the Chetak EV, became the largest electric two-wheeler maker in the country. It was followed by TVS Motors, with both overtaking Ola Electric, which had been the runaway market leader the past few years.

“These shifts underscore the intensifying competition, with incumbents leveraging their established brand equity, distribution networks, and manufacturing capabilities to reclaim market share from newer entrants,” says Harshvardhan Sharma, head of auto retail practice at Nomura Research Institute.

Troubles in recent times, caused largely by concerns over the safety of vehicles, and a shift in what Ola refers to as its registration practices have led to a slowdown in its sales. Till March 17, sales of Bajaj Auto totaled 10,510 units, ahead of TVS Motor (8,888) and Ola Electric (7,020). In March, a total of 39,622 electric two-wheelers had been sold in the country at the time of finalising this story.

So far in 2025, Bajaj has sold 54,348 electric two-wheelers, while TVS has sold more than 52,500, and Ola about 40,800.

“Now customers prefer reliability, quality of product and service experience over everything. That means established players, with their large network, better serviceability and experience, have a better proposition,” says Vinay Piparsania, founder and principal of MillenStrat Advisory & Research, and a former executive director at Ford India.

What happened to Ola?

In December 2020, Ola Electric signed a memorandum of understanding with the government of Tamil Nadu to set up a manufacturing plant in the state to produce electric vehicles. In January 2021, it identified a 500-acre plot in Krishnagiri, a hamlet in Tamil Nadu, and over the next few months, worked at breakneck speed to build what it called the world’s largest two-wheeler factory. In August 2021, it launched two models: Ola S1 and Ola S1 Pro, at an introductory price of ₹99,999 and ₹129,999 respectively. After state subsidies, the price to consumer for the Ola S1 came to ₹79,000. The two models were based on the AppScooter, made by Netherlands-based Etergo, founded in 2014, which Ola had acquired in May 2020.

“In the EV space, the only way we can create impact is to play the scale game,” Aggarwal had told Forbes India in an interview in March 2021. “Because, unless you build at scale, you cannot bring the cost down enough, and you cannot get consumers excited.”

“In the EV space, the only way we can create impact is to play the scale game,” Aggarwal had told Forbes India in an interview in March 2021. “Because, unless you build at scale, you cannot bring the cost down enough, and you cannot get consumers excited.”

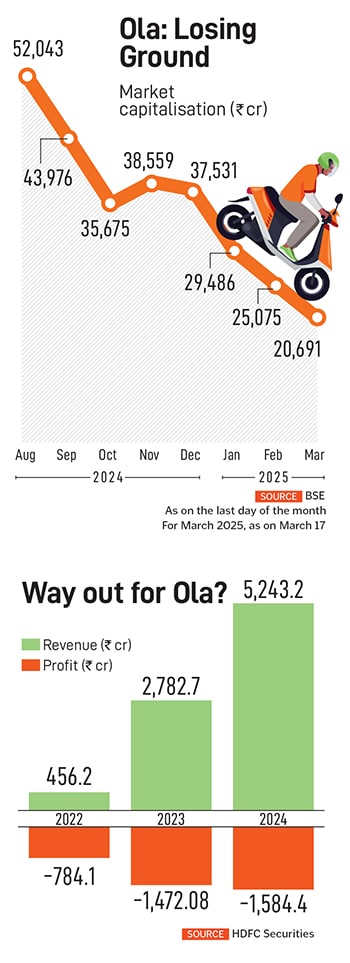

Soon enough, Ola Electric Mobility attracted the attention of global private equity heavyweights, raising funding from the likes of SoftBank and Tiger Global before deciding to go public last year. The IPO was a success. Sales of Ola’s electric vehicles had been on an upswing.

In 2024, nearly 1.1 million electric two-wheelers were sold in the country, of which Ola sold more than 400,000, giving it about 35 percent share of the market. But by December, Bajaj and TVS had usurped the top spot.

“This is perhaps the toughest time for Ola,” says Puneet Gupta, director at S&P Global Mobility. “The traditional players have entered the market and are relying on their dealer networks to up their game. But if you look at the market, there is still a long way to go, and it is possible that we might see Ola hit back.”

Ola has also been hit hard by customer complaints. The consumer watchdog, Central Consumer Protection Authority (CCPA), ordered a probe into alleged deficiencies in the company’s services and products. The CCPA had received more than 10,000 complaints over a year-long period.

“First impressions in the automobile industry are difficult to get rid of,” adds Piparsania. “Customer behaviour is changing, and companies which chose to focus on a gradual and measured approach, along with the backing of their robust structures and service networks, are beginning to appeal to customers.”

That has meant consolidation in the electric two-wheeler segment, which had been fragmented with many brands, and emergence of five strong players. Take, for instance, Hero Electric, an early mover in the segment, which had managed to capture as much as 60 percent of the market by 2019 with sales of nearly 50,000 units. It recently went bankrupt.

“If you see, there were some hit-and-run players,” Sharma of Bajaj Auto says. “They have all gone now. They were 50 percent of the industry three years back, now they are 10 percent. These were people who were just slapping things together and were in something of a trading mode.”

Also read: Can India’s electric vehicle makers take on Tesla?

Bajaj’s rise

Bajaj’s recent rise has come despite serious hiccups.

“If you are a first mover for a certain period of time and you have secured the first-mover advantage at a very high cost, it means nothing. I think it’s important to get the proposition and financial architecture right because sustainability in the end comes from the financial architecture. You can become number one. But to stay number one, you must make money,” says Sharma of Bajaj Auto.

The company forayed into the segment in late 2019 with the Chetak, a brand that had helped build the Bajaj legend when buyers waited years for its scooters. Weddings were planned around the availability of the Chetak—an essential dowry item—until the influx of 100 cc motorcycles from the late 1980s onwards led to the decline of scooters.

The launch of the Chetak EV, however, did not go as planned. Covid-19 put the company’s electrification plans into disarray. By January 2023, Bajaj was back at the drawing board to resurrect the brand.

“We were still struggling on the supply chain side,” Sharma says about the lull between 2020 and 2023. “There were two factors. One was getting the supply chain and vendor system right. And as we were completing that, we felt our cost architecture was not right to press on.”

Chetak, he says, has a metal body and ranks high on safety. “Fundamentally, it comes down to the product,” adds Sharma. “Our proposition is that it should be life-proof. The category is such that there is a lot of anxiety on performance or thermal accident or battery.”

While many of the early movers in electric two-wheelers, driven by private equity funding, aggressively pursued the market even though costs spiralled, Bajaj chose not to splurge. “To some extent, we were saying that everyone is losing huge amounts of money,” Sharma says. “Why should we lose so much money and be number one? It is okay to lose less money and be number three and when we turn positive, we can step on the accelerator and drive to the number one position, which is what we have done.”

That measured approach helped the company’s EV arm turn Ebitda positive. Ebitda is short for earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortisation—a key indicator of financial wellbeing. Today, 25 percent of Bajaj’s domestic revenues come from electric, with CNG vehicles accounting for another 19 percent. “If you see the kind of stake we have in making this business sustainable, no other company has that,” says Sharma.

Bajaj expanded its dealership network for electric vehicles from around 100 to more than 500 within a year, making them more accessible to customers. Says Sharma of Nomura: “Longstanding manufacturing expertise allows for efficient scaling of EV production, meeting market demand effectively.”

Ola Electric’s S1 e-scooters at its manufacturing facility in Pochampalli, Tamil Nadu

Ola Electric’s S1 e-scooters at its manufacturing facility in Pochampalli, Tamil Nadu

Image: Varunvyas Hebbalalu / Reuters

What now?

A new EV subsidy scheme, PM E-Drive, announced in October 2024, provides a subsidy of ₹10,000 for each electric two-wheeler sold until March 2025, which will be brought down to ₹5,000 next year. Several states offer additional subsidies.

Two other brands that have dominated petrol two-wheelers, Hero MotoCorp and Honda Motorcycles and Scooters India, are stepping up their play in the segment after being on the fringes. That would mean strategies for all two-wheeler makers would converge at some point, and practices such as deep discounting, which manufacturers often rely on, could be a thing of the past.

“Till the time everyone converges onto the same page and is running the business with a similar dashboard, you will have a variety of competitor strategies,” Sharma of Bajaj says. “So, we feel that this is a period we must go through. But that equilibrium is coming in a year or two years. It is not far off now.”

With charging infrastructure growing, albeit slowly, electrification will continue to grow though not as rapidly as expected in the past. “I don’t think the growth is going to be very sharp,” Sharma says. “The penetration of electric scooters is 20 percent of ICE scooters. It will perhaps grow in 12 months’ time to between 22 percent and 25 percent. At that kind of a rate, it will be growing faster than ICE (internal combustion engines) scooters, but it won’t be in a vertical manner.”

Meanwhile, the overall two-wheeler segment is slowly growing to embrace multiple fuel options with electric and CNG getting added to ICE. “We will have to have multiple systems,” adds Sharma of Bajaj. “We are not suspending any ICE programmes and our new product development in ICE must thrive while our new product development programme in electric must be vibrant.”

Even then, it would be imperative to have the likes of Ola slugging it out in the market, taking the fight to the legacy manufacturers. “Ola’s contribution to the electrification of two-wheelers is certainly commendable,” says Gupta of S&P. “They had put enough pressure on the incumbents and pulled the entire ecosystem forward. If they don’t exist, there is the risk of traditional players going slow on the EV push.”

That means the top spot in India’s fast-paced electric two-wheeler market is still up for grabs. As Sharma of Bajaj says, “The real number one is somebody who has a strong competitive ratio, which can then be translated into business value.”