I first met him in 1995, after he had taken over as chairperson of Tata Sons in 1991. I was the secretary to then Union Minister of Industry and former chief minister of Kerala (K Karunakaran). The License Raj had been dismantled and the liberalisation process had started, but there were many fetters still on the Indian industry. Many industrial leaders would come calling on my minister in Delhi. I never took special notice of anyone in particular, until this man walked in one day, immaculately dressed in a suit, a white shirt and a blue tie. He was astoundingly good-looking, spoke in soft tones, and tried to downplay his status. One thing about RNT was that when you spoke with him, he made you feel as if you were the most important person in his life at that time. From then on, we kept in touch and met frequently, exchanging ideas. During one such meeting in 2018, where we had dinner, he gave a fascinating account of his life after which I told him to write his autobiography. He said ‘if you want, you write the biography’. It was simple happenchance.

By 2018, he was not holding any executive position. So, I sat with him for some meetings, but most of the things, he recounted for me. Towards the last few months, age normally takes its toll, but initially—from 2018 to around 2021—he shared everything in meticulous detail. He had a photographic memory.

Q. How did Tata conduct his business meetings? Was he consensus-driven, or did he lead people to come to a decision?

He never forced a decision. He consulted his advisors, and if he found that they needed to analyse things differently, he used to nudge them towards that point of view. He never took a decision without hearing everybody. During the acquisition of Corus (steel and metals manufacturer), he went from chair to chair, telling everybody [in the Group] to carefully consider the deal, and that he would not go forward if they had a difference of opinion. By doing so, he was able to aggregate the collective wisdom of the intellectual resources of the Group. There is no question of him being dictatorial.

Q. Whom did he turn to for making business decisions?

He relied on two people most of the times. For strategy, it was RK Krishna Kumar (former Tata Sons director). For financial matters, he relied on NA Soonawala (former trustee of Sir Dorabji Tata Trust and Sir Ratan Tata Trust), who had worked with Tata in the initial phase to devise ways to increase the stake of Tata Sons in their large companies.

Q. Who from the current leadership of the Group reminds you of Ratan Tata?

Undoubtedly, the present chairperson [of Tata Group], N Chandrasekaran. Both are very subtle, amiable. They are not boisterous people, but deep thinkers. Both of them have identified the rails on which the Group would move to the next level: Technology. RNT had identified technology as a means to transform the company in the 1990s, and today Chandra is leveraging it to be at the forefront in the digital world. RNT told me that Chandra is the master of the times of the digital world. He is also a dyed-in-the-wool Tata in terms of philosophical moorings.

Also listen: Ratan Tata’s impact on Indian auto industry

Q. Is there a story emblematic of Tata’s leadership style that did not make it to the book?

One quality emblematic of his leadership was compassion. His mother, Sooni Commissariat, died of cancer. She was in Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in the US. During a critical time of her treatment, the Center’s director, Edward J Beattie, had gone for his holiday. RNT felt that if he were present at the time, his mother could have perhaps lived for some more years. After he came back to India, Tata wrote a warm letter to Beattie, saying that he believed the tragedy could have been avoided if the doctor were present during this time. Yet, he said he would like to welcome the doctor to his country and do everything possible to make his visit fruitful and memorable. That was Tata’s style, reconciliatory and understanding. His humility disarmed people.

Q. What did Ratan Tata view as his shortcomings as a business leader?

According to me, it was his compulsive desire to do everything the right way. He had confessed that his decision to stay away from the selection committee for Cyrus Mistry was a big mistake because he was an idealist. The second time his idealism got him into problems was when he chose West Bengal for the Nano factory. He wrote to the then CM [Buddhadeb Bhattacharjee], saying he wanted to create more than 10,000 jobs and rebuild the industrial base of the state, but being socially conscious, without looking at the dangers involved in taking such a decision, was a problem.

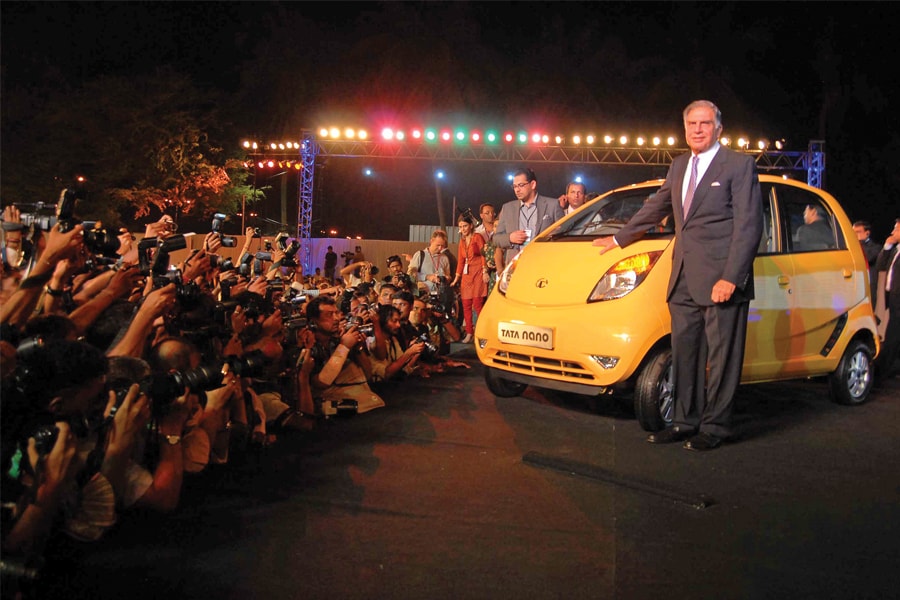

Ratan Tata unveils the Tata Nano in Mumbai, 2009

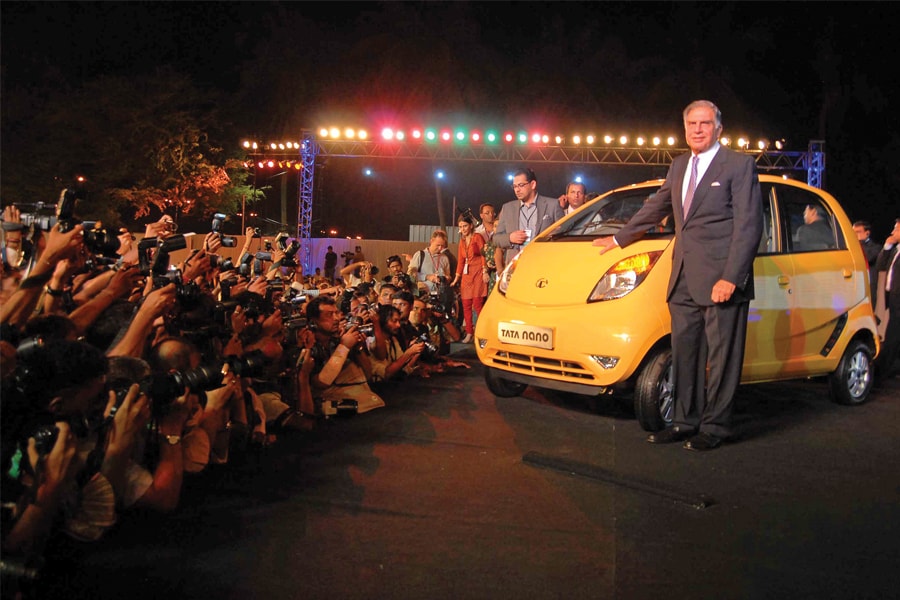

Ratan Tata unveils the Tata Nano in Mumbai, 2009

Image: Abhijit Bhatlekar/Mint via Getty Images

Q. Would he have done things differently today if he had the opportunity?

I personally believe, and many people in Tata Motors still believe, that if RNT had continued as chairperson for another four to five years, it [Nano] would have been a success. Girish Wagh [of Tata Motors] has said that RNT’s never-say-die attitude would have turned the Tata Nano into a resounding success.

Q. The book released after Tata’s death. Did you show him what you had written, and what could have been his reaction?

I cannot second-guess, because by 2024 RNT had become old… but before that, in the initial phase when we used to discuss, he told me that this was my interpretation of his life. I used to ask him several things to get the record straight. The book is dense because it has a lot of data…anybody can write prose, but we should back it with empirical data. Tata himself was not aware of the phenomenal growth of the Group under his leadership. He called me and said, ‘It warms my heart to know that my hard work has yielded result for the company, the shareholders’. So, he would have been happy [with the book], but he may have said that I have gone overboard in praising him in some places. But I am not interested in his approval. I am reflecting what Henry Kissinger or others say about him. RNT was very uncomfortable if anybody praised him, but that does not mean I should not praise him when praise is due.

Q. Was making it hagiographical a concern?

I started writing this book as an independent project, receiving no monetary benefits from Mr Tata. I funded it entirely from my own pocket, because I did not want to be accused of giving Tata more praise than what is due. A person like me owes nothing to Mr Tata or the Group. In fact, in a manner of speaking, they owe me, because I spent four-and-a-half years of my life because of my great respect for him.

Q. How much did you spend researching the book?

I spent almost ₹70-75 lakh from my own pocket because I travelled across the world and put a few research staff. If I spend four-and-a-half years of my life and if I am not able to produce a book that will stand the scrutiny of people—and insulate myself from the accusations that this is a paid job—I would not spend so much money, because it is an impartial work. There are many media articles calling the book a hagiography—one article also said the reason RNT did not approve the book was because it was hagiography. My answer is to point me one place where I have praised him where praise is not due. Forget if it is a hagiography or RNT-approved, look at the quality of research, and ask [if] each assertions [are] being substantiated. That is the only question you need to ask, because, in fact, if RNT had approved the book, it would have lost its normative value, its independence.