The financial crisis in Gensol Engineering once again reinforces the need for founders to cede control in favour of transparent governance as soon as they raise public or institutional capital.

The financial crisis in Gensol Engineering once again reinforces the need for founders to cede control in favour of transparent governance as soon as they raise public or institutional capital.

Imaging: Kapil Kashyap

The deepening crisis of financial irregularities, fund embezzlements and fraudulent transactions in Gensol Engineering reveals severe corporate governance failures highlighting how promoters prioritised personal gains over the interests of investors and lenders. Weak internal controls and lack of regulatory compliance, perhaps, are rapidly trapping Indian startups into such crisis.

This time, the cracks are deep. It may significantly impact retail investors’ money, leading to major losses. As in most companies engulfed in a crisis, retail shareholders are left holding the baby. Ditto for Gensol Engineering.

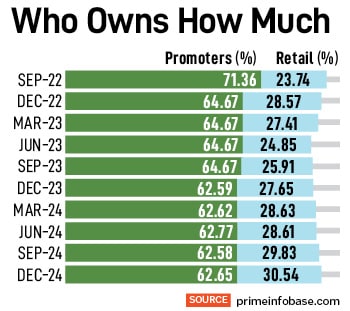

In the December quarter of 2024, retail investors were the largest public shareholders in Gensol Engineering, holding 30.54 percent stake in the company that provides engineering, procurement, and construction (EPC) services to the solar power sector. Surprisingly, even the Enforcement Directorate (Raipur) held 5,20,063 shares, or 1.37 percent stake, in Gensol Engineering at the end of December 2024.

The increase in retail shareholding has been gradual, shows a Forbes India analysis of data of the last 10 quarters provided by Prime Database. At the end of September 2022, retail shareholding was at 23.74 percent. Adding to the woes, recently the company had announced stock split of its shares in the ratio of 1:10, which is likely to attract more retail investors to the scrip. However, Securities and Exchange Board of India (Sebi), in its interim order on April 15, has put stock split on hold.

“The retail investors now facing significant losses were exposed due to a lack of transparency and late regulatory intervention. Sebi’s Investor Protection and Education Fund (IPEF) mechanism is reactive, not preventive,” Sonam Chandwani, managing partner, KS Legal & Associates says.

She explains that the legal options for shareholders now include filing class-action suits under Section 245 of the Companies Act, 2013, to seek compensation for misleading financials and the lack of disclosures. Shareholders may also file complaints with the Sebi grievance redressal facilitation SCORES platform, demanding accountability from the company’s board and auditors. “In case of fraudulent misrepresentation, invoking Section 447 of the Companies Act (punishment for fraud) will initiate proceedings against the promoters,” Chandwani explains.

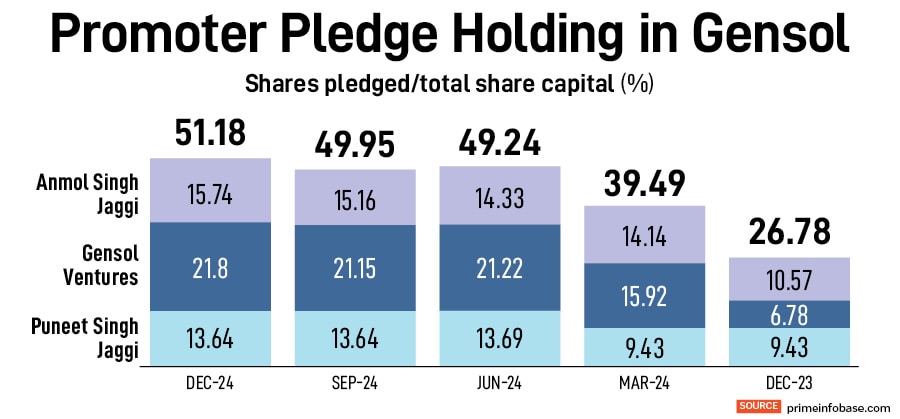

As of now, the market regulator has removed promoter brothers Anmol Singh Jaggi and Puneet Singh Jaggi from holding the post of directorship or any key post in the company. The Jaggi brothers and the company are barred from accessing the securities market.

As of now, the market regulator has removed promoter brothers Anmol Singh Jaggi and Puneet Singh Jaggi from holding the post of directorship or any key post in the company. The Jaggi brothers and the company are barred from accessing the securities market.

Sebi will also appoint a forensic auditor to examine the books of Gensol and its related parties, which will be required to submit a report within six months from the date of appointment.

Last June, the market regulator had received a complaint relating to the manipulation of share price and the diversion of funds from Gensol Engineering and, thereafter, started examining the matter. “The promoter holding in the company has already come down substantially and there is a risk of the promoters further off-loading the shares on gullible investors,” Ashwani Bhatia, whole-time director, Sebi says in the interim order.

The market regulator also says in the order that, prima facie, evidences of the blatant violation of the rules of corporate governance are writ large over the workings of Gensol. The diversion of funds by promoter entities reflects a culture of weak internal control, where even ring-fenced borrowings from institutional creditors were rerouted at the total discretion of the promoters. “The internal controls at Gensol appear to be loose and through the quick layering of transactions, funds have seamlessly flowed to multiple related entities/individuals,” Sebi says.

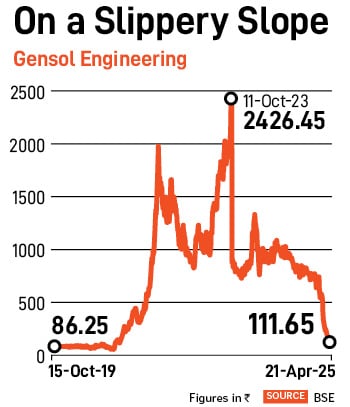

During the past year, the share price of Gensol Engineering touched a high of Rs 1,126 a piece with a market capitalisation of around Rs 4,300 crore. The stock has slipped 95 percent from its lifetime high of Rs 2426.45 on October 11, 2023. It has lost 39 percent in April alone and 85 percent in this year so far.

Gensol was initially listed on the BSE SME Platform on October 15, 2019, which subsequently migrated to the main board of BSE and NSE on July 3, 2023.

Both Gensol Engineering and BluSmart are promoted by the Jaggi brothers. Started in 2012, the company is the flagship of the Gensol Group. Besides EPC services to the solar power sector, it diversified into electric vehicles (EV), setting up an EV production facility in Pune for manufacturing two-seater electric fleet cars and cargo targeted at the ride-hailing market and the logistics sector.

Also read: Sebi’s new panel to review conflict of interest

Lack of corporate governance

Chandwani points out that the financial crisis in Gensol Engineering once again reinforces the need for founders to cede control in favour of transparent governance as soon as they raise public or institutional capital.

She adds that the delay in unearthing the fraud is partly systemic. “Auditors, who are legally bound under Section 143(12) of the Companies Act to report fraud to the Central Government, often succumb to promoter pressure or maintain silence under the garb of ‘professional judgment’,” she elaborates. This highlights a regulatory gap in the rotation and independence of statutory auditors. “Furthermore, audit committee and independent directors (under section 149 and 177) bear statutory responsibility for failing to flag red flags indicating a lapse at every level of oversight,” she says.

The prima facie findings of Sebi shows the mis-utilisation and diversion of funds of the company in a fraudulent manner by its promoter directors, the Jaggi brothers, who are also the direct beneficiaries of the diverted funds. The market regulator says the company attempted to mislead Sebi, the credit rating agencies, lenders and investors by submitting forged conduct letters purportedly issued by its lenders.

The prima facie findings of Sebi shows the mis-utilisation and diversion of funds of the company in a fraudulent manner by its promoter directors, the Jaggi brothers, who are also the direct beneficiaries of the diverted funds. The market regulator says the company attempted to mislead Sebi, the credit rating agencies, lenders and investors by submitting forged conduct letters purportedly issued by its lenders.

Sebi’s findings also reveal how the promoters, their related parties and relatives benefitted from the funds of Gensol, a listed company, through layered transactions. Such transactions were required to be disclosed, which Gensol has allegedly failed to do. “What has been witnessed in the present matter is a complete breakdown of internal controls and corporate governance norms in Gensol, a listed company. The promoters were running a listed public company as if it were a propriety firm,” it says.

The company’s funds were routed to related parties and used for unconnected expenses, as if the company’s funds were promoters’ piggybank. The result of these transactions would mean the diversions mentioned above would, at some time, need to be written off from the company’s books, ultimately resulting in losses to the investors of Gensol.

“While the fund diversion primarily occurred in the context of EV purchases intended for leasing to a related party, the risk it creates is neither isolated nor contained. The company has a substantial order book, comprising critical infrastructure contracts awarded by government and public sector entities in the renewable EPC space,” Sebi says.

These contracts are not just capital- intensive, they also require strict financial discipline, timely execution, and reputational credibility to retain project flow and institutional trust.

According to Sebi’s prima facie evidence blatant violation of rules of corporate governance is writ large over the workings of the company. “The diversion of funds of the company by promoter entities reflects a culture of weak internal control, where even ring-fenced borrowings from institutional creditors were rerouted at the total discretion of the promoters. The internal controls at Gensol appear to be loose and through the quick layering of transactions, funds have seamlessly flowed to multiple related entities/individuals,” it says.

Eroding investor trust in startups

The lack of internal controls and major discrepancies of corporate governance in startups in India have been rapidly on the rise. According to Chandwani, the recurring wave of corporate governance failures in startups, particularly those with rapid capital inflows and aggressive growth targets, stems from weak internal checks, over-dependence on promoters, and, most critically, insufficient board oversight.

“The startup ecosystem, though innovation driven, has often sidelined robust compliance in favour of speed and valuation, creating fertile ground for misconduct. Investors, especially institutional investors, must mandate governance covenants at the term sheet level and insist on quarterly forensic reviews, board independence, and audit committee disclosures to safeguard against such risks,” she stresses.

She adds that as BluSmart is being closely linked to Gensol’s business and finance, its operations and credibility are bound to suffer collateral damage. If found complicit or financially intertwined in the fund diversion, it may face regulatory scrutiny or investor withdrawal. “Startups like BluSmart must now proactively subject themselves to voluntary disclosures, special audits, and forensic reviews to retain investor confidence and business continuity,” Chadwani says.

She adds that as BluSmart is being closely linked to Gensol’s business and finance, its operations and credibility are bound to suffer collateral damage. If found complicit or financially intertwined in the fund diversion, it may face regulatory scrutiny or investor withdrawal. “Startups like BluSmart must now proactively subject themselves to voluntary disclosures, special audits, and forensic reviews to retain investor confidence and business continuity,” Chadwani says.

Tarun Singh, MD and founder, Highbrow Securities, says the Gensol case is not an isolated incident—Byju’s, once India’s most valuable edtech startup, now stands accused of similar excesses: Alleged financial opacity, delayed audits, and reports of lavish spending while employees and vendors went unpaid.

“These cases are symptoms of a deeper malaise. Startups, especially in their early stages, operate in a regulatory grey area where oversight is minimal, and the line between personal and company finances is often blurred. The argument that future profits will justify today’s excesses is not just flawed—it is dangerous,” Singh adds.

He argues that if promoters can freely dip into company coffers under the assumption that future profits will cover their tracks, then every startup and listed firm becomes a potential Ponzi scheme—where today’s theft is masked by tomorrow’s promised returns.

How the financials look

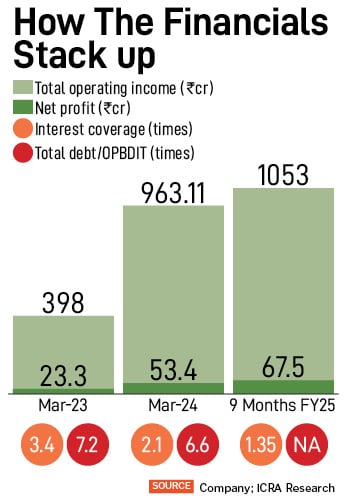

On a standalone basis, Gensol sales have grown to Rs 1,152 crore in FY24 from Rs 61 crore in FY17. During the same period, its operating profit went up to Rs 209 crore from Rs 2 crore, while net profit also escalated to Rs 80 crore from Rs 2 crore.

Its total liabilities/balance sheet size to Rs. 2,202 crore in the first half of FY25 expanded from Rs 10 crore in FY17. During this period, Gensol’s borrowings increased to Rs 1,045 crore in the first half of FY25, after touching Rs 1,260 crore in FY24. In FY17, Gensol’s borrowings were nil.

Credit rating agencies, Care Ratings and ICRA, downgraded the ratings assigned by them for fund-based and non-fund based credit facilities availed by Gensol to ‘D’ as delays in servicing debt obligations. The agencies had also stated that when they sought term loan statements, Gensol provided statements of all lenders except those of Indian Renewable Energy Development Agency (IREDA) and Power Finance Corporation (PFC).

Credit rating agencies, Care Ratings and ICRA, downgraded the ratings assigned by them for fund-based and non-fund based credit facilities availed by Gensol to ‘D’ as delays in servicing debt obligations. The agencies had also stated that when they sought term loan statements, Gensol provided statements of all lenders except those of Indian Renewable Energy Development Agency (IREDA) and Power Finance Corporation (PFC).

However, Gensol had immediately denied “any involvement in falsification claims” made by the ratings agencies. It had also responded to them that it was regular in its debt servicing and that the default by BluSmart had no impact on the company.

Out of Rs 977.75 crore from IREDA and PFC as term loans, Rs 663.89 crore was said to be utilised for purchasing 6,400 EVs. As per the submissions made by Gensol, EVs were procured and subsequently leased to BluSmart, a related party. However, later Gensol acknowledged that it had procured only 4,704 EVs.

NSE visit and missing EV plant

On January 28, Gensol had said that it received pre-orders for 30,000 of its newly-launched EVs. However, Sebi’s investigation showed it was just memorandums of understanding (MOUs) entered with nine entities for 29,000 cars with just an expression of willingness and no reference to the price or delivery schedules.

A representative of NSE had also visited the plant site located in Pune on April 9. It was found during the visit that there was no manufacturing activity and only two-three labourers present there. “The NSE official called for details of electricity bills of the unit and it was observed that the maximum amount billed by Mahavitaran during last 12 months was Rs. 1,57,037.01 for December 2024. Hence, it can be inferred there has been no manufacturing activity at the plant site which is on a leased property,” Sebi says.

So, what is the way forward for the listed entity now?

According to Chandwani, if the fund diversion in Gensol is proven, Sebi may direct disgorgement under Section 11B of the Sebi Act and initiate prosecution. “The company may face delisting pressures, and revival would need a complete promoter overhaul, special audit, and board reconstitution, supervised by Sebi,” she says.

Investor recovery may be slow unless a new buyer is brought in under IBC or a scheme of compromise is approved.